It is tempting to consider trouble on screen exclusively from the perspective of film and TV representations. On the one hand, the indiscernibility of fact and fiction causes distrust in representations. On the other hand, representing the problems generated by this blurred line seems to be the obvious solution. This can be observed, more and more often, in films or TV series that focus on this very cognitive problem, treating the deceiving power of screen representations as central to the plot (Black Mirror, Mr. Robot, Darknet, Westworld, etc.) The trouble with screens, then, is that they are caught in a vicious circle that also seems irremediably closed – exposing the dysfunctional reception of representations by embedding screens within each other may lead to the very misperception that the operation seeks to prevent. To balance this view that the dysfunctional dimension of audiovisual representations belongs in the storyworld, in the mediating space between the viewer and the screen, or, in the worst case, in both the former and the latter, I want to examine here the kind of trouble that is mainly located off-screen – even though it is produced by a certain type of interaction between viewers and interfaces. In what follows, therefore, I do not mean to study the proverbially blurred line between the factual and the fictional on-screen, nor the consequences of the induced confusion on viewers’ level of belief or distrust towards all forms of mediated representation, but a new type of embedding, as it were: the confusion induced by the fact that our screens are used to mediate different types of content, each defined by a factuality/fictionality ratio. This confusion also has an impact on audience reception, which will be the main object of the present chapter.

My motivation goes beyond what may seem to be the desire to revert perspectives on an often-studied issue. It lies in the intuition that, while troubled representation has been studied from the standpoint of its impact, for instance its potential for change (e.g., when dystopia acts as a warning or as a prompt to behave differently as a society), the receiving end has been largely neglected in comparison, especially when trouble appears in the reception process without obviously being provoked by problematic representations1. Consequently, and to put it rather simply before delving into the complex entanglement of production and reception that characterizes the problem and case studies at hand, I seek to place the emphasis on situations of troubling reception – a phrase that describes at once odd reception patterns and the induction of parasitic elements in reception processes. As I seek to demonstrate in this chapter, the very act of interfering with reception processes is exposed as a result of studying cases of problematic reception. Although such cases arise in a variety of contexts, I will mainly focus here on instances of media interference that have an impact on current social and political issues. Through the examples examined here, I seek to demonstrate that studying troubling reception cases reveals the mechanisms by which they are generated, in a way similar to that in which the unveiling of extra layers of meaning brings to the surface the complex operations through which meaning is structured.

A Theoretical Framework in Need of an Update?

Of course, I am not ignoring Stuart Hall’s work on encoding/decoding, especially the parts on negotiated and oppositional audience responses, which are largely considered to have generated convincing and final conclusions on problems very similar to the one under study. According to Hall:

The codes of encoding and decoding may not be perfectly symmetrical. The degrees of symmetry – that is, the degrees of ‘understanding’ and ‘misunderstanding’ in the communicative exchange – depend on the degrees of symmetry/asymmetry (relations of equivalence) established between the positions of the ‘personifications’, encoder-producer and decoder-receiver. But this in turn depends on the degrees of identity/non-identity between the codes which perfectly or imperfectly transmit, interrupt or systematically distort what has been transmitted. The lack of fit between the codes has a great deal to do with the structural differences of relation and position between broadcasters and audiences, but it also has something to do with the asymmetry between the codes of ‘source’ and ‘receiver’ at the moment of transformation into and out of the discursive form. (Hall 166).

I have reproduced the quotation at length to show how adequate it still is in many respects to make sense of troubling reception. Indeed, in Hall’s encoding/decoding system, static in the reception process is caused by a ‘lack of fit’ between the source code and the receiving code, in particular when receivers choose a code that clashes with the source’s – for instance in the case of an ‘oppositional’ reception mode.

Troubling reception, I argue, cannot be reduced to such a ‘lack of fit’. For this reason, I suggest here that Hall’s theoretical model, as it focuses on structural difference, can be seen as incomplete (for example, because it does not clearly describe the nature of the link between the dominant code and hegemonic ideology), or at least in need of an update. In a paper given at the International Communication Association Conference in Boston in 2011, Sven Ross already suggested a revision of the model that drew a clear distinction between oppositional reception as “text relative”, and oppositional reception as ideology-driven (S. Ross). There are, however, numerous other ways in which the model could be revisited. For instance, amended versions of the model could take into account the possibility that some decoding strategies are the result of a thought-out decision by the decoding party; or they could consider the current trend, where oppositional strategies are provided for by the producers of texts in their encoding strategies – typically, conspiracy-theory thinking is an oppositional mode that media producers may encourage to make their products even more popular with forensic audiences. This necessity for yet another update, which also provides the incentive for the present article, comes from the appearance of new communication strategies that seek to influence reception from within and, in so doing, to preempt the very possibility for an oppositional stance to be adopted. As a result, cases of ‘a lack of fit’ remain exceptions.

In the cases studied below, this operates at the level of encoding/decoding, where the differences between specific codes are elided, and has superstructural consequences, whereby an ideology is invisibly promoted. The second part of the process is not new, as readers of Benjamin or Adorno, and more generally of Marxian critical theory are well aware. The first part of the operation, however, arguably illustrates a new way of obtaining the same hegemonic kind of effect. Indeed, new ways of imposing reception patterns seem to have emerged, which may deter or prevent alternative reception in ways Stuart Hall could not have thought of, in the absence, in his time, of the transmedia configuration that later allowed for new cases to appear. As I will seek to demonstrate through several case studies in which the same issue arises, although each time with a different set of parameters where the encoding/decoding pattern is concerned, the current mode of influence stems from new types of interfering with the level of ‘fit’ between stable expression (often, but not exclusively, in the form of screen representation) and potentially unstable reception. All those cases involve ways of using resemblances between media forms or platforms to plant an encoding pattern beneath another and alter reception stances, turning them into playful or sophisticated decoding processes that barely deserve, as a result of this modification, to be described as “oppositional” any longer. My hypothesis is the following: intervention in the form of troubling reception has all the more impact as this veneer of postmodern self-consciousness and playfulness paradoxically makes it difficult for viewers to become aware of the new ways in which cultural hegemony yields forms of political power.

My main argument is that this troubling trend comes from the palimpsestic overlapping of three culturally dominant notions: surveillance, reality TV (or televised reality), and intermediality. Standard definitions of surveillance apply here – I will, however, operate with notions of technologically-aided, in particular televised, i.e. visual and remote, monitoring of activities, before introducing notions of metaphorical surveillance. I will use Misha Kavka’s definition of reality television – ‘the term refers to unscripted shows with nonprofessional actors being observed by cameras in preconfigured environments’ (Kavka 5) – especially in the areas where it overlaps with televised reality (which can be provisionally defined by deleting the notion of ‘preconfigured environments’ from the above). The point is to recall how close reality TV is to surveillance, on the one hand, and to underline that the notion of external intervention, whether before, during, or after the shooting, largely depends on the audience’s reception posture. In other words: reality TV was initially promoted as surveillance turned into entertainment, but most viewers are now aware that a lot more fiction than may at first seem is injected while making the programs. Its reception is oppositional, although accepted – or one could say that it is acceptedly oppositional, as viewers take satisfaction and pride in the assertion that they know better, and derive pleasure from spotting signs of scripting in their favorite reality shows. The oppositional stance, in that case, is what makes the viewing pleasant, and viewers do not expect, let alone want, reality shows to be less fictional and more real. Simply put: the code should be maintained, the better to be opposed, an operation that provides a huge share of the pleasure of watching. Similarly, surveillance has from the start been diverted from its aim (protection) and perverted in its function due to the interference of alternative – multiple, and not always oppositional – reception patterns. The first example that comes to mind is, of course, the use of surveillance for voyeuristic purposes, for example, in reality TV shows. The third concept, intermediality, has been defined in various ways. I have chosen here the definition that works best to place the notion at the nexus of surveillance and reality TV (the overlapping of which I have just highlighted, with ‘reality’ as the main common denominator). The definition is by André Gaudreault: ‘Intermediality is, in a minimalist acceptance, this concept which designates the process of transfer and migration, between the media, of forms and contents […], a standard to which any mediated proposal is likely to owe part of its configuration’ (Gaudreault 175, my translation).

Visualizing Troubling Reception

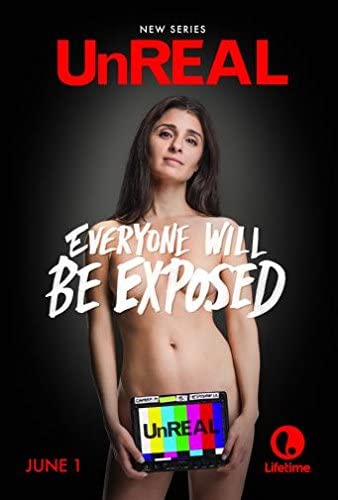

In the cases studied here, intermediality allows for the transfer of contents and forms from surveillance to reality TV, or vice versa, and, as a side-effect, from screen to reality. Naturally, to allow for such transfer, several screens often interact. A good example to introduce troubling reception is the Lifetime TV series UnREAL (2015-18). UnREAL is an American program about the making of a TV game show, Everlasting, which is clearly reminiscent of the famous dating show, The Bachelor. The season one poster brilliantly visualizes the implications of the show’s entanglement of surveillance, television, and reality, while suggesting potential effects on reception (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

The poster presents the main character, producer Rachel Goldberg, in the nude facing the camera. The season tagline covers her breasts. It says: ‘everyone will be exposed’. The phrase provides a good illustration of reality TV’s intricate connection with the idea of the naked truth, as encapsulated in the play on words. On the show, various levels of deception will be exposed, but the truth will be naked only by name. As in the poster, body exposure will remain partial. Despite the full frontal, breasts are not offered to the gaze, and Rachel’s lower belly is hidden from view by a tablet used to monitor the shooting of the TV show live (the device is connected to all the cameras on the set). Thus, the notion of ubiquitous vision, borrowed from CCTV to spice up reality shows, is qualified by the role of the very device that is supposed to endow its owner with omnivision, the tablet, which once again blocks the voyeuristic gaze. Voyeurism is presented to be located mainly in the apparatus, so that exposure will have to remain figurative. At least, such are the rules of any regular reality show. Even if the backstage approach of UnREAL suggests that the usual limits may be exceeded on the show, the embedded tablet, a screening device that screens body parts away from view, acts as a reminder that the surveillant gaze, in a reality TV context, operates within limits. And so on and so forth: the various levels of mise-en-abyme included in the poster are as many ways of delaying access to the actuality of the real beyond the surface of mere televised reality, and of asserting that the realness of reality TV is primarily a matter of perspective. More specifically, it is, in this case, a matter of reception. Any on-screen reference to the popular aesthetics of reality TV encapsulates the notion of the panoptic gaze of surveillance. In turn, surveillance includes the possibility for captured content to serve as evidence (to ‘expose’ misdemeanor). Or, the mode of reality TV prompts, or at least includes as a possibility, the reception pattern of surveillance, which may in some cases be the reception of pictures as evidence. In reality TV, surveillance places viewers in the position of perceiving reality in the raw, without offering completely objective representations. The poster thus encapsulates one of the tenets of troubling reception – toying with potentialities contained in the resemblance between various types of screen content to induce a specific viewing pattern.

Troubling Transfer Patterns: The Handmaid’s Tale and ‘metoo’

The Handmaid’s Tale’s contextual insertion, and especially its connection with the ‘MeToo’ movement, constitutes a variation on the same principle. The serial adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel is one of the most commented-on TV shows of the last decade. Upon its release, viewers and reviewers noted its political scope, or at least its political pretension. The producers of the Hulu drama acted on the perception of the series, playing up the show’s political importance to turn it into an increasingly profitable operation. Adding new seasons, despite the fact the first one had adapted the whole of Margaret Atwood’s novel on which the show is based, was a way of acknowledging the show’s political appropriation by viewers. Early on, The Handmaid’s Tale was perceived as an allegory of the United States, a vision of its present and of its future. The trend has shown no sign of abating since. The series’ projection is grim and pessimistic. Press releases and fan comments alike see Gilead, the show’s dystopian society where women are reduced to their childbearing role, as an illustration of America’s inability to protect their rights. According to this dominant reading, the show provides, at best, a depiction of the Gilead that America is to become soon – this is the speculative angle. At worst, it is an implicit depiction of what America has already become – this is the allegorical viewpoint. In both cases, viewers are urged to respond, ideologically and politically, to protect such basic rights as abortion or take legal action against the potential consequences of rape culture. Such responses are not surprising. The Handmaid’s Tale almost naturally reads as a warning. It delivers a barely implied criticism of the condition of women in Trump’s United States. Many press articles about the show exaggerate the parallelism between Gilead and the USA, claiming that the show is not a metaphor, but that it feels real or even that it is reality (Nowakowski; Lifshutz; Friedlander; Dray; Nelson). These comments are sometimes amplified by the lead actress on the show, Elizabeth Moss, who incites people to ‘wake up’ because ‘Gilead [is] happening’ (Mulkerrins), and of course, by Atwood’s own comments in various press releases, the latter being more nuanced as a rule.

A brief study of the show’s media coverage since its release conducted on the MIT engine mediacloud.org shows the parallel between Gilead and the US to be the dominant reading. A more specific search across global English-language media for coverage that connects The Handmaid’s Tale and ‘MeToo’ shows the copresence to be extremely prevalent. The keywords that appear most frequently next to the above are, unsurprisingly, ‘harassment,’ ‘Weinstein,’ and the vocabulary of the show-business-industry awards, suggesting that the show’s acclaim by the profession is in proportion with its symbolic feminism. Besides, coverage that connects the show with women’s rights issues flourishes in the context of progressive campaigns (or in anti-reactionary campaigns, for instance to warn against banning abortion again in certain states). This is particularly clear if one focuses on left-wing press coverage, where extra emphasis is placed on Weinstein-related and harassment issues, but also on Trump, with frequent mentions of two of the torchbearers of the ‘MeToo’ cause, Natalie Portman and Frances McDormand. The right-wing press, by comparison, does not draw a connection between the show and the 45th American president, but repeatedly labels the show as ‘feminist’ – using the term as a negative attribute. One article, in particular, reveals that viewer perception of how rooted The Handmaid’s Tale is in reality depends on party affiliation (Shevenock).

The series is undoubtedly a useful political instrument: it deals with social issues and works to spread tolerance. I would like to complement this consensual reading with an alternative one, tinged with a bit of cynicism. I argue that the connection between The Handmaid’s Tale and American politics is all but contained. It receives far too much emphasis to keep passing as implicit. The link is even exploited by the show’s detractors, who try to turn the argument against it by presenting The Handmaid’s Tale as a feminist dystopia (Doten; White; Howard; Howard; Cottle), a reproductive dystopia (Weigel), or a criticism of the oppression of women in Saudi Arabia (Sainato and Skojec). But even then, the show is always interpreted from the viewpoint of its resemblance with America, albeit to claim that it is not about the US and try to thwart its political agency. This is the case, for instance, in a National Review article entitled ‘Art for Politics’ Sake’: ‘The hyper-literalists at Vanity Fair helpfully summarized the author’s thoughts under the headline “Margaret Atwood Says The Handmaid’s Tale Was a Warning for the Trump Era,” but, really, did they need to spell it out? With all the warnings flying about, I’m ready to burn a Bible every time I see a pregnant woman’ (Hillard). Even when a conservative publication exposes the show as part of a deliberately liberal strategy, its link with reality is strengthened as a result.

With the trailer for the third season, the show started displaying a different type of anchorage in US society. The trailer’s voice over directly references Ronald Reagan’s 1984 re-election campaign, full of bright promises for the future, tinging the show with ironic overtones ahead of the new season’s broadcast. A W blog post digs out the intention behind the promotional clip: ‘The Season 3 Trailer Spoofs Ronald Reagan’s 1984 Campaign Ad’: ‘‘It’s morning again in America,’ a man’s voice narrates. ‘Today, more women will go to work than ever before in our country’s history. This year, dozens of children will be born to happy and healthy families’’ (W magazine). With the season 3 trailer, The Handmaid’s Tale uses a cultural reference to TV politics and ties Gilead with Reagan’s America as a result, in addition to the usual connection with Trump’s presidency. Implicitly, Trump’s policy is exposed as backward. Intermedial content transfer operates once again, from real TV campaigning (Reagan) to a fictional TV series we are incited to perceive as televised reality. Cleverly, the show thus endorses accusations of anti-Trump leanings. Indeed, the intermedial shift triggered by the trailer expresses self-disculpating awareness that the third season, even more so than the previous two, is likely to be read as a long pro-Democrat campaign clip.

Admittedly, the trick is too obvious, as is the intended impact on viewers, for the reception of the show to be very troubling. It may be, I suggest, because another aspect of the show’s reception is at once easily detectable and far more troubling. The Handmaid’s Tale, although a high-profile series, is show business as usual. Throughout its seasons, however, the makers of the show have managed to incite viewers to read it as serious, ominous, and deeply political. The series was thus defined as necessary. While all those attributes apply, it is no mean feat to plant in viewers a reception pattern that leads them to believe the show is tantamount to political commitment, all the while leading them to forget that it is primarily part of a business operation. The Walt Disney Company owns Hulu, on which the show is broadcast. With such shows as The Handmaid’s Tale, Disney buys itself the label of political activist. Viewers can comfortably believe that they do not watch Hulu for personal pleasure, but for the benefit of the community, and for America’s future. An interesting collateral effect is to strengthen the impression that the business of the entertainment industry is political, which may seem to retroactively explain why entertainment and TV politics have coalesced for decades (S. J. Ross; Troy). Crucially, presenting the consumption of the show as a political act makes viewers more likely to subscribe to Hulu (and celebrities all the more likely to dabble in politics).

Intermedial Collusion: House of Cards and Putin

In the next case study, the interaction between TV and politics reverses the one exemplified in the previous section. As TV screens and media were rife with coverage of the presidential primary, a fake campaign commercial – in fact, the trailer for House of Cards’ fourth season, released in March 2016 (Frank Underwood 2016 House of Cards Netflix Ad Season 4) – led Kevin Spacey, and his character Frank Underwood, to steal the show (Greiner). The trick was simple: Underwood, the fictional president of the US running for a second term in the fictional universe of the TV drama, appeared in what looked exactly like a regular campaign spot, as if the character was really running for president. For Shaun Seixas, ‘Netflix was able to hijack the media and America’s attention to briefly refocus the spotlight from Donald Trump to the upcoming season of House of Cards and its main attraction […], Frank Underwood’ (Seixas). Netflix tapped into viewer attention where they thought it was likely to be located, placing itself subtly on the continuum of entertainment and politics that the American presidential campaign has been for decades.

The trailer provides material that is readily transferrable from the context of TV politics to that of TV series, with the notion of TV promotion acting as a midway point. On the first level of reading, House of Cards thus jocularly poses as a reading of contemporary politics that is self-consciously designed to make money. On the second level of reading, the dimension of self-parody denies that House of Cards exerts political influence – it is, viewers are supposed to conclude from the trailer, just a show. The latter would seem incidental if Kevin Spacey, in numerous TV interviews, had not so constantly asserted that the show was not a political tool, but that it was just a commentary on US politics, which merely ‘invites comparison’ (Hoffman; Conlan). As a result, the trailer seems to confirm his denial. Such insistence in claiming that the show is about politics, but not politically committed, may be related to troubling instances in which House of Cards had indeed proved its efficiency as a political instrument. Accusations leveled against the show for trying to tilt the political balance in favor of the Democrats abound in web articles and on YouTube.

To provide the best illustration of the show’s ability to turn the tide of real-life politics, I have chosen to focus on the sad case of Tom Schweich, documented, for instance, in a May 2015 GQ article (Zengerle). Schweich, a Missouri auditor who was running for governor in 2016, committed suicide before the actual election. Many commentators blamed the Republican candidate’s death on a nasty radio ad by an action committee calling itself ‘citizens for fairness.’ The radio ad involved a narrator who mimicked Frank Underwood’s voice. An archetypally Machiavellian Democrat on the show, Underwood said in the ad that Schweich was a weak candidate, and that the moment he got nominated, the Democrats would put their candidate in his shoes. Beyond the dramatic outcome, the tragedy proves Frank Underwood’s political influence. As with the season 4 trailer, influence is obtained through an ad that resorts to a fictional character and induces a specific perception of real-life politics. In the Schweich case, the content transfer from the show to political campaigning exploits the notion that all politicians are corrupt and that many real-life Democrats are like Frank Underwood, i.e. that they can pull all the strings, and even manipulate a Republican candidate to ensure victory. In this case, the most common reception of the show (where Frank Underwood is undoubtedly villainous and corrupt) is distorted by content transfer (Underwood’s voice and tone is imported from the show into a libelous radio ad) to put trouble in the reception of real-life politics. Thus, a self-proclaimed noncommittal TV show is turned into a lethal political weapon.

The same as with The Handmaid’s Tale, the trend has been coeval with the show’s duration. More recently, the impact of the TV show has extended well beyond the often-underlined negative impact on people’s perception of American politics as essentially dishonest. It was revealed in early 2019 that Russia had sought to influence the 2016 presidential election in the USA via Twitter. The now available tweets, produced by Russian troll farms to deter traditionally Democratic voters from going to the polls, provide evidence of Russian intrusion. Most of them suggested that the Democratic candidate would be a traitor to the causes of ethnic minorities or women’s rights. Recently revealed information suggests that the whole trolling strategy may have been largely based on the observation of House of Cards’ likely negative impact on American citizens’ political culture, especially where democratic candidates are concerned (Burgess). The process can be simplified as follows: given the increasing appeal of Netflix with viewers, and the excellent approval rates of its political show House of Cards, which happens to focus on a democratic political couple, a risk-free way of discrediting a democratic candidate is to tap into the popularity of the show. In his book All the Kremlin’s Men, Mikhail Zygar claims that Putin insisted his advisers watch House of Cards – and another TV show focused on a proverbially corrupt democratic politician, a real one this time, Chicago Mayor Daley as he is depicted in the critically acclaimed Starz Tv series, Boss (2011-12). ‘“You’ll find them useful,” the president recommended. It is clear why Putin liked them: they affirmed his belief that Western politicians are all cynical scoundrels whose words are bad values and human rights of pure hot air and simply a tool to attack enemies’ (Zygar). After watching the show, Putin’s ‘men’ would better understand the Washington microcosm, all those scheming men and women whose way of thinking they would therefore be able to penetrate.

The strategy can be considered to work because House of Cards lends itself to such simplification as the one applied by Putin. For him, the level of scripting used by the showrunners is kept to the bare minimum. It consists in creating characters that are only slightly larger-than-life. In the case of House of Cards, and from Putin’s perspective: Frank Underwood is just a little more corrupt than average; the First Lady is the somewhat hyperbolic version of all First Ladies, who invariably seek to replace their husbands as presidents of the US; Frank’s henchmen do not in the least recoil at the prospect of committing murder for their boss; investigative journalists are tougher than Woodward and Bernstein were with Nixon, and so on and so forth. Given the unmissable points of resemblance between the show and famous political figures or historical situations, it is quite easy to present it as a type of mockumentary on American political life.

More specifically, the Russian disinformation strategy is mostly about forcing or reinforcing the notion of an implicit correlation between House of Cards’ fictional presidential couple and the Clintons (Stern). This effect is all the easier to achieve given the number of conspiracy theories surrounding the political careers of Bill and Hillary. The latest one, ‘linking the Clinton family to the death of multimillionaire and accused sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein,’ is supported and propagated by American president Donald Trump (Diamond). Like the Underwoods, the Clintons seem to have built a presidential dynasty, whose rise to power culminated, or at least should have culminated, in Hillary’s election for president. The First Lady’s rise to power is indeed implicitly hinted at in the trailer to House of Cards’ 6th season (the true reason, of course, is that lead actor Kevin Spacey was evicted from the show after being accused of sexual harassment, which explains why his wife on the show had to take prominence – but then again, how Frank and Claire kept scheming as a couple made this a possible, not to say a likely outcome). Indeed, as Romano points out, ‘many of the campaigns undertaken by the IRA [a well-known Russian troll factory suspected of intervention in the 2016 American presidential campaign] involved anti-Clinton propaganda, as well as the process of infiltrating and further polarizing already polarized Internet communities on social media’ (Romano). Besides, and despite statements to the contrary by the creators and actors of the TV show, some of his interventions in the media make room for the suspicion that Kevin Spacey is actually a strong supporter of the Clintons (Chozick; Kreutz), which strengthens the notion that Underwood is Clinton-like and mechanically, that the Clintons are, like him, deeply corrupt. One immediately perceives the detrimental power of inciting voters to perceive American politics through the lens of the TV show, the way Russian tweets and the extreme right press entice us to do.

It transpires from such a reading that the perception mode the TV show entrenches in its viewers is once again close to that of reality TV. In this case, forcing this perception mode has unprecedented effects on reality. Putin, as it were, invited members of his crew to watch House of Cards as a political reality TV show recorded in the White House and revealing the secrets harbored in the corridors of power. By inducing a reception of House of Cards along similar lines, i.e. as some kind of political reality show, the element of corruption that belongs in the fictional program becomes a character feature that can be readily ascribed to real-life politicians. In the process described here, the Russian administration also engaged in a form of surveillance of American political life that is organized from far away but that provides access to real information. In a way, it takes me back to the connection between surveillance and reality TV from which I started, except that the perceptive mode of reality TV here serves to perform indirect surveillance through a fictional program, where reality-TV viewers watch in surveillant mode for signs of the real beyond the illusion of reality they are being fed. Russia gathered information from the political TV show, declared it reliable, and eventually proved effective to favor Donald Trump by estranging the Democratic candidate Hillary from some of her traditional grassroot supporters. The transfer from the reality TV mode to the surveillance mode results not in that viewers perceive the Underwoods as providing a fictional grid that throws light on the Clintons (although this is one side-effect, this is just the type of reading that expands the meaning of the work, rather than its impact on the real), but in that viewers perceive the Clintons as the real-life inspirations for the Underwoods (whatever the type of media in which they appear, the Clintons will henceforth be perceived as manipulative politicians). Take away a level of fictionalization that is presented to be negligible, and viewers may think the two perfectly match.

Conclusion

In this article, I have introduced troubling reception, a strategy that forces decoding patterns into viewers in order to impact reality, for a variety of purposes. It operates by exploiting intermediality as a content transfer mechanism that relies on the blurred areas between media forms. I have focused primarily on the cases of surveillance and reality TV, but the reasoning applies to other types of screen mediation and to other types of mediation altogether. In all the cases studied here, reception is troubled because of the similarity between media forms, which makes it easy to transfer content from one to the other, so that content is received from the perspective of the wrong medium, to produce specific effects on viewers.

This observation challenges some classic notions of cultural studies. Indeed, I argue that effects theory here resurfaces under a new form, as screen fictions are seen to exert a new type of impact. Conversely, Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding model fails to apply. Indeed, the reception of shows or films seems to be under some form of control, but not so much because the production frames the reception, nor because viewers are subservient to some ideology or hegemony. The cause, rather, is that guidelines on how to receive the show are intermedially and therefore invisibly scattered over different platforms.

There is a scent of conspiracy theory to this conclusion. To qualify this impression, consider an aspect of all the above case studies – the overlapping areas between forms of screen mediation always come with embedding patterns that can show awareness of the potentially manipulative process at hand. It appears that when considered from this angle, the process of manipulating reception can always operate alongside a self-reflexive approach that takes into account the viewers’ increased awareness of encoding processes. Troubling reception, in the end, also exists as a virtual development of the intended reception process into a state of awareness by viewers that their favorite show is pursuing a specific impact on them. To put it differently, troubling reception is always on the verge of becoming meta-reception, an interpretive pattern that is able to put an end to the troubling suspicion that a worldwide manipulation of cultural productions is undergoing.