In Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, the celebrated introductory aerial shots of the little Torrance Volkswagen winding up the road to the remote Overlook Hotel foreshadow Jack’s tortuous and torturous journey through the hotel’s and America’s history. As many critics have repeatedly pointed out, the meandering trajectory of the whole family driving up to the Wild West Rockies also inscribes on screen the characters’ twisted mindscapes – and first and foremost Jack’s growing mental disorder (Jack Nicholson). The opening extreme wide and high angle shots are already indicative of some higher force, some all-seeing, ubiquitous predatory eye seemingly monitoring Jack and his family from above.

Fig. 1. The tiny Torrance Bug winding its way up the Rockies in Kubrick’s film

The scene has since become a mainstay of American cinematography and popular culture forever announcing some seminal moments in the protagonists’ lives. In the finale episode “Everyone is Waiting” of Alan Ball’s 2005 TV series Six Feet Under, the camera’s tilt-up from Claire’s car leaving Los Angeles for New York and a new life as a photographer to a white sky/frame resembles a fade-in and inscribes absolute finality in a simple, irreversible way. Although much less ominous, the heroine’s itinerary chronicles the sum of human crises and deaths of the family members the serial format lends itself to so well. Just like in the ending of Kubrick’s Shining where Jack is framed in the 4th of July photo, Ball’s celebrated show similarly ends with a set of photos hanging on the wall and showcasing the present moment which is already gone but somehow, forever dormant. In a clear metafilmic allusion to the photographer-director’s work, the showrunner’s cycles of aerial shots and photographs seize the attention of the viewers. The latter can thus launch into their own constructive editing which, in turn, underscores the notion of eternal recurrence and temporal trap.

In Kubrick’s cult movie, the early traces of disturbance emanate from the first sequence as unsettling images of unknown events well up uninvited and inscribe themselves into the frame. In both the filmic and serial formats, Kubrick’s 1980 film and Garris’s 1997 three-part miniseries, the dividing line between realistic family drama and horror genre dissolves and is somehow uneasily blurred from the outset. The inscription of trouble and abnormality however diverges widely in the two versions. Much more straightforward, showrunner Mick Garris’s representational strategy resolutely foregrounds the conventions of horror. For Garris, working on the miniseries meant acknowledging Stephen King’s dissatisfaction with Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of the source novel and hence correcting yet another type of “problem” – Kubrick’s now legendary circumventing of King’s primary interest in the conventions of supernatural horror. The first corrections were then applied by King himself as he wrote what he thought to be the “correct” television script.

The echo of some past murder immediately showcased in the first scene of the 1997 miniseries deliberately steers the rest of the storyline in the horror category direction. Still, the generic ID cards of the two opuses can be confusing as their codes are often diverted from their original functions and remain unstable. Poised between horror and comedy, they both defy categorization. To what extent do they truly fit the horror genre as the storyline highlights alcohol addiction, destructive madness and various forms of personal and historical “haunting”? And when much of the performance of Kubrick’s Jack relies on humor and comedy and when Garris’ series oscillates between a chronicle of resident evil and an exploration of human beings’ “dark sides”?

In this study, I will examine how the two works’ very diverse strategies foreground the psychological but also historical and formal crises at the heart of the narrative and the types of odd forms of generic hybridity and transformative levels of manipulation they display – including manipulation of the viewers. The palimpsestic work of adaptation links up with the notion of corrections, the screenwriters’ as the intradiegetic caretakers’, in as much as it induces various forms of trouble. The uneasy relation of the two screenplays to the original text and to each other allows for haunting variations and echoes turning the works into the very source of creating trouble.

The troubles

The term refers to the supernatural and paranormal abilities and afflictions that often run in the bloodlines of the characters in the TV series Haven (2010-15) created by Sam Ernst and Jim Dunn on Syfy and Showcase and which was freely adapted from Stephen King’s novel The Colorado Kid (2005).

In Kubrick’s version, the superimposition of the wild surroundings onto the family members’ faces and bodies is the first sign of dysfunction. As they progress upward, the dissolves operate some sort of visual graft signifying the danger of displacement and potential disintegration of the characters’ selves as they get closer to the haunted space of the Overlook hotel. The dissolve technique and the wide shots of the wild landscape forcefully underline the disturbing status of space and its intricate relation to people’s lives – and deaths. Thus, the very notion of “trouble” is first visually inscribed on screen before the unfolding of the narrative.

Fig. 2. First signs of dysfunction in the opening of Kubrick’s film: blurred images and superimposed subjective and objective worlds

Functioning like a full-fledged character, space becomes all the more parasitic and pregnant as the Rockies’ high-key chromatic range is deceptively welcoming. The shot actually looks like a ghost photograph and materializes early on in the frame the toxic and oppressive grip the environment starts gaining on the protagonists from the onset. Even though its encroaching presence is first visually underlined before it can be directly narratively addressed, the story Jack tells about the Donner party already functions as one of the spectral traces the representational strategy relies on. The fact that the party’s members had to resort to cannibalism in order to survive while crossing the Sierra Nevada in 1846-47 foreshadows Ullman’s story about the caretaker Charles Grady. In a bout of “cabin fever” in wintertime, the latter butchered his entire family. The way in which the odd parallel is drawn ushers in the first instance of unnatural connection between the surroundings and the hotel’s living memory. From the start, the viewer is clearly made aware of the eerie contiguity between spaces and layers of time allowing major traumas to resurface cyclically. The ghostly superimposition of shots also highlights the characters’ own dysfunctional relation to a type of space providing in a somewhat devious way what Eudora Welty calls a fundamental sense of place. It shows space being irretrievably connected to Time, or rather the hold of a peculiar but still imprecise time dimension over space and eventually a specific kind of place. In her 1997 essay Place and time: The southern writer’s inheritance, Welty discusses Time’s hold in these terms: “[…] farther back than history, there is the Place. Place is seen with Time walking on it—dramatically, portentously, mourningly, in ravishment, in remembrance […]” (Welty).

Instead of feeling rooted in the new western territory they are given to discover and finding an empowering sense of belonging, the protagonists start questioning its impact: Jack by eagerly embracing the dark side of its history and focusing on the hotel’s grisly scrapbook and Wendy (Shelley Duvall) and Danny (Danny Boyd) by instinctively refusing to become integral part of it.

The reference to the ill-fated Donner party is the first in a list of historical events which all link the hotel premises to tragedy, from the desecrated Indian burial ground it has been forcefully built on, to the various deaths of famous and unknown people that took place in it over the decades. The aerial shots of the car’s second ascent redouble the first when Jack left for his interview. This time, the entire Torrance family is on board. They foreshadow the way in which time suddenly expands in the Overlook realm and narrative levels eventually start interfering with each other. The past contaminates the present to such an extent that past stories keep reincarnating themselves: already as we saw an iteration of the Donner party story, the Charles Grady story Ullman reluctantly tells prefigures Jack’s own redoubling efforts to fit in the original narrative pattern.

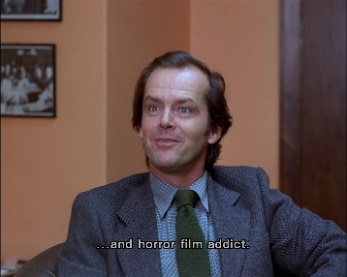

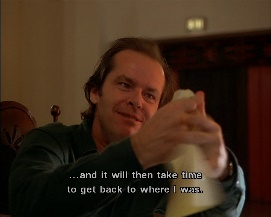

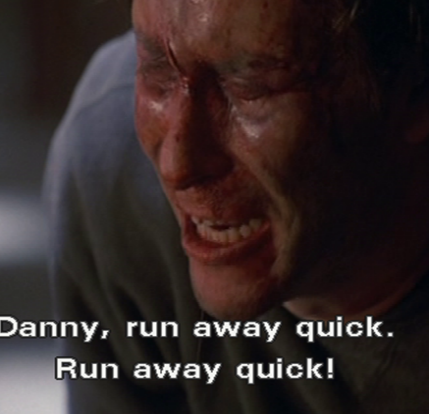

Fig. 3-5. Kubrick toying with the horror genre’s conventions and mocking the viewer as “a horror film addict”: Danny’s first horrific visions of the Overlook

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Jack’s candid reply that there is no chance such a traumatic past could affect him or his family and his mocking remark about his wife being “a horror film addict” ironically contrasts with his son’s first traumatic experience of the Overlook’s evil. Irony here is applied as a corrective factor which mitigates the troubling impact of the horrific images. This moment of generic uncertainty in between family drama, comedy and horror materializes a locus of conflict between competing generic identities which, as Rick Altman says in Film/Genre, activates “both cultural and generic standards” (Altman 152). Thanks to parallel editing, the scenes with Danny in the Denver bathroom reinsert the codes and conventions of horror into the narrative. Danny’s hallucinogenic flashes of a blood-soaked elevator and of the two enigmatic sisters in blue are meant to be perceived as simultaneous and illustrates the way the director is also manipulating, and mocking, the spectators who are eager viewers/detectives loving to be manipulated and to embark on hermeneutical quests. Their intrusion into the frame also demonstrates how Kubrick makes the notion of crisis available to the viewer. The contiguity of the visual and narrative-within-the-narrative dimensions magnifies the incremental logic of each particular genre, horror and the supernatural as well as drama.

If Kubrick seems to be mainly interested in the banality of human evil, Garris and his teleplay writer King choose to focus from the outset on a kind of dormant evil turning viral when reignited by Jack’s personal demons. The film’s opening is intensely visual and the hauntingly ponderous notes of Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind’s score “Dies Irae” and the subsequent electronic and orchestral piece “Rocky Mountains” prove to be chilling companion pieces to the sublime landscape. The series’ first sequence however consists in another kind of hauntological sonic landscape testifying to the absent-present traces of ghosts that Jacques Derrida discusses in his 1993 Spectres of Marx. The opening features no image track at first and the impact on the viewers is instantaneous. The disjunction of time and space is made manifest by a score seemingly disconnected from Jack’s visit of the hotel basement. It instantly immerses the spectators in a murder scene they know nothing about. The dark screen denies them the possibility of being rooted in any kind of realistic space but still, provides a fertile environment for the fragments of some malignant past that survived to resurface. As Stephen King underlines in his book on the anatomy of horror, Danse Macabre, it’s a form of evil which is “simply there” (King 214). It precipitates the resurgence of ghosts lost in a time Derrida also identifies as being “out of joint” after the scene when Hamlet talks to his dead father in act I, scene 5. These spectral aural fragments of the buried past immediately provide what the source novel author calls “the basis for our most primordial fears” (King, Danse Macabre 182). The sonic hauntology technique introduces the viewer to some unseen locus horribilis the voices of the undead rise from and which will grow like cancer within and around the main protagonists. Such dislocation of time and place at the Overlook seems to be foregrounded in a much more direct way than in Kubrick’s version. The notion of trouble irradiates straight from the hotel, whose heart is the unruly boiler room. From the outset, it is framed as a huge antiquated time machine functioning as a central backdrop; its malignant heart is immediately made visible by the use of parallel editing forcibly linking the hotel’s troubled past to Jack Torrance’s present.

Fig. 6. The boiler room in the hotel’s bowels: parallel editing forcibly yoking past and present

While the haunted pictures are first mediated by the boy in the film, they simply rise to the surface of the screen in the miniseries. The intercutting of the murder and suicide scenes with the realistic shots of the basement materializes the first departure from a rational reference frame which merely exacerbates the stock-in-trade coding of some demonic force welling up to take control of the lives of human protagonists. It somehow “corrects the problem” of Kubrick’s and Johnson’s revised storyline as the former caretaker Delbert Grady would say, by flatly adhering to King’s original plotline. When Jack asks the handyman whether there are ghosts, besides scandals and deaths at the Overlook, the latter denies it, providing the necessary tension between the surface story and what’s left untold to move the narrative forward. In both mediums, the ghosts’ emergence is then inscribed on screen very early on but the nature and representational strategies of the haunting are rooted in fundamentally different conceptions of the origin of what King calls “those deep-seated personal fears ̶ those pressure points ̶ we all must cope with” (King, Danse Macabre 131).

Lost

Differing methodologies of inscription of the types of connection between reality and imagination and space and Evil are at work in the two opuses. In Signatures of the Visible, Fredric Jameson underlines the power of the filmic form as a medium for the critique of culture and the diagnosis of social life. Undoubtedly, the long-form retelling also fulfills a similar function, especially as it gives more leeway for character development. Jack more particularly becomes the choice repository of what King calls “those things which trouble the night thoughts of a whole society,” “More often the horror movie points even further inward, looking for those deep-seated personal fears ̶ those pressure points ̶ we all must cope with. This adds an element of universality to the proceedings, and may produce an even truer sort of art” (King 131). His increasingly distorted grasp of reality becomes the focus of conflicting representational modes in the two versions. In Kubrick’s adaptation, Jack is from the start a profoundly unhinged character – one, we quickly learn, who has broken his son’s arm in a drunken bout and whose aspiring writer’s block fuels his social and personal frustration and inbred violent streak. The director’s disjunctive, cryptic visual grammar provides a mostly hermetic assemblage which only captures stations in the itinerary of a protagonist displaying signs of madness already there, just like the evil force in the miniseries is already there. The Steadicam’s gliding effect and the treatment of close-ups bring vividly to life the full force of this mental deterioration. Jack, at work or having a nightmare in his bedroom for instance is framed from a variety of angles and often captured from behind–as if to render palpable the materiality of the other world he’s slowly being drawn into. But how to represent this parallel universe and its fundamentally other nature was one of the greatest areas of disagreement between the two creators as King made abundantly clear:

Parts of the film are chilling, charged with a relentlessly claustrophobic terror, but others fall flat. […] Not that religion has to be involved in horror, but a visceral skeptic such as Kubrick just couldn’t grasp the sheer inhuman evil of the Overlook Hotel. So he looked, instead, for evil in the characters and made the film into a domestic tragedy with only vaguely supernatural overtones. That was the basic flaw: Because he couldn’t believe, he couldn’t make the film believable to others (Norden).

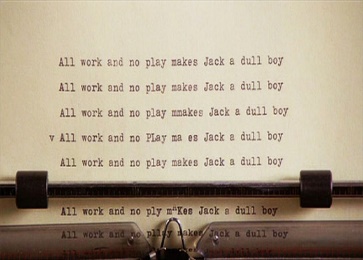

Throughout the movie, the camera inscribes on screen diverse variations on the already much commented-on maze motif. However the “labyrinth of words” is possibly the most literally mindbending version of it. The endless replication of the written words on the page is first merely hinted at: Jack is at his desk obsessively writing his alleged play–but Wendy and the viewer don’t know yet that he’s rewriting the same words over and over again. The unbroken word chain materializes on the page the inescapable entanglement of time and space at the Overlook and Jack’s loss of bearings.

Fig. 7. Double-framing the characters: the encroaching Overlook environment reflected in the pages of Jack’s manuscript

Even though the viewer expects some form of supernatural component in the scene of the row between Jack and Wendy who keeps interrupting him in his work, the entire exchange is played against the codes of the horror genre: Kubrick’s “exquisite sensitivity to the nuances of light and shadow” (King, Danse Macabre 115) merely foregrounds the incipient mental derangement in a blocked writer who feels despised and unappreciated. No dark atmosphere provides “the basis for our most primordial fears” (King 182). A low-key style of lighting steers the viewer’s interpretative quest in the family and psycho drama direction. But the fact that Jack tears up the pages he was writing surreptitiously reinstates the figure of sterile reiteration and the central motif of the maze with its (literal) dead ends. The scene with Wendy discovering the nearly identical pages comes later, toward the end of the Wednesday section of the movie: their grisly nature and the slight variations on the form and spacing of the words on the page, “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”, operate as some perverted parody of autobiography in part masquerading as a grotesque biopic. The haiku format of the one-line text ironically condenses a twisted imaginary “biophoty”, a term French critic Joanny Moulin derives from Hayden White’s “historiophoty.” In his 1988 article “Historiography and Historiophoty” in The American Historical Review, the latter defines “the representation of lives and our thoughts about them in visual images and filmic discourse” (Ibid.). It reflects Jack’s complete disorientation but also the viewers’ general confusion before this semantic maze which is both an icon--it’s technically a photogram or series of photograms--and an emblem, a totally hermetic representative symbol of some alternate reality.

Fig. 8. The nonsensical infra maze-like universe of a sick “autobiography” in the Wednesday section

The same (extreme) close-up technique allows the viewer to delve into Jack’s nightmarish mindscape and his literally mind-bending tale within the story. Such an exploration of the mind’s camera obscura finds its source in the short story collection Nightmares and Dreamscapes published by Stephen King in 1993 and released on TNT as an eight-episode miniseries in 2006. The zoom-in on this miniaturized universe paradoxically magnifies the scale of the Overlook’s hold. The shot of the scrapbook containing newspaper articles on the portentous history of the Overlook and sitting prominently on Jack’s desk in the lower left side of the frame brings an additional layer which further encloses the protagonist in a dangerously destabilizing story still unfolding and a murderous history foregrounding the notions of historic recurrence and repetitive patterns in the history of a given space. Both King and Kubrick toy with the operative notion of repeat occurrence as theorized by Mark Twain:

NOTE. November, 1903. When I became convinced that the “Jumping Frog” was a Greek story two or three thousand years old, I was sincerely happy, for apparently here was a most striking and satisfactory justification of a favorite theory of mine—to wit, that no occurrence is sole and solitary, but is merely a repetition of a thing which has happened before, and perhaps often1.

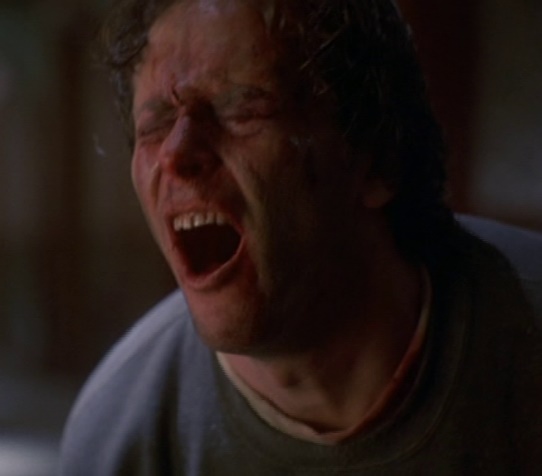

What happens at the Overlook is a ripple effect from the past which keeps echoing and resurfacing under various guises on the hotel grounds. The camera brilliantly registers on screen the contiguity of a number of very diverse types of space: Jack’s realistic environment as he is writing his play, the encroaching evil world of the Overlook as Jack and Wendy are framed by dwarfing open doors and panels and the actual boundaries of the product of his deranged mind, the page framed in extreme close-up. Ultimately however, what the camera emphasizes is the total spatiotemporal disorientation exacerbated by the current family crisis of a character trapped in some kind of inner mental loop. The latter reflects all of the hotel’s timelines at once – the 1920s, the 1970-71 Delbert Grady murders’, and the present with the Torrance family members. Kubrick’s Jack is lost in the meanders of his own liquor-addled brain early on while in Garris and King’s miniseries, character is rather a function of the demonic agents which control the Overlook so that Jack’s itinerary is mostly shaped by the codes and conventions of the horror genre. Most of the serial narrative tracks the transformations and “corrections” the protagonist undergoes but also imposes on his wife and son during his horrifying “descent into madness through the malign influence of the Overlook” (Norden Ibid.). The term “corrected” is a seminal one as the previous caretaker Grady uses it to tell Jack how he forever disciplined his wife and daughters. In the same way, the narrative applies its own corrections to the original storyline of the source novel and the intradiegetic one. In the series, the inscriptions of Jack’s increasingly distorted face on screen not only connote altered states of consciousness (daydreams and nightmares, abject cruelty, fanaticism, madness, dread…), but also mostly contribute to exposing the unshakable sway the dark forces have over the character. For Stephen King and showrunner Mick Garris, the radical otherness of Jack’s masks signals the deconstruction of his core identity and mostly the rise of what King calls “the sheer inhuman evil […], the malign influence of the Overlook, which is like a huge storage battery charged with an evil powerful enough to corrupt all those who come into contact with it” (Norden Ibid.).

Fig. 9-11. The many facets of Jack’s reality: variations on possession and indeterminacy

Fig. 10.

Fig. 11.

The character’s itinerary and the director’s postures dictate what the camera captures in the frame – which brings the viewer back to the use of horror codes: Garris inscribes the progress and regress of the hotel’s evil entity in a very literal way, just as he films ghosts incarnate literally taking (over) human flesh. Ghosts no longer function as mere cryptic signs of some alternate reality forever eluding the spectator: they become a reality, the actual precondition for comprehending (and enjoying) the Overlook’s tragedy. One of the most eloquent scenes in an otherwise longish and often unintentionally amusing series (the moving hedge animals are probably the funniest) happens during the final showdown between the possessed father and his resisting son. The camera materializes the perennial fight between Good and Evil by showing actor Steven Weber alternate between the part of the loving father and his evil personas. Like the eerie characters from the masked ball who haunt the hotel space, Jack himself becomes a variation on a series of masks which can’t ever be fully deciphered, including by himself.

Jack becomes an aberration, a necessarily ungraspable representation, just like the ghosts he did not perceive as such. The hermetic viewer who would follow on Jack’s footsteps is therefore warned: Jack’s incapacity to accept the complex nature of the signs surrounding him has condemned him to be locked in a system of self-referential signs, seemingly disconnected from any reality. (Jaunas 88).

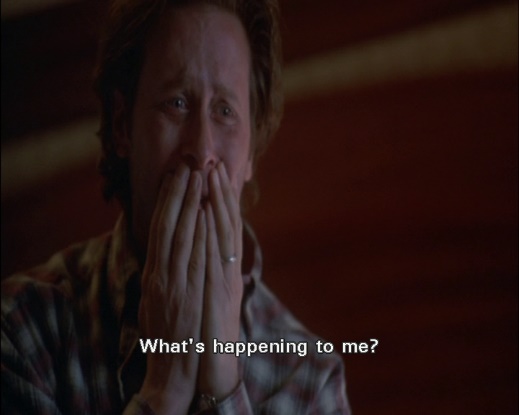

As he faces his son in a devastating standoff at the end of the show, Jack ejaculates, “What’s happening to me?” Ontological uncertainty is at the heart of the TV series in much more graphic and highly codified terms than in Kubrick’s movie. The Oscar-winning makeup supervisor Bill Corso applied gory special effects and prosthetics to Steven Weber’s face and body, rendering Evil’s trajectory all the more visible. To a certain extent, the technique materializes in a highly specific way what Mario Falsetto calls the “process of spatialization” (Falsetto 79) in his narrative and stylistic analysis of Kubrick’s films. As locations function metaphorically for the characters in the movie, so is Evil materialized as being relentlessly at work in the miniseries. The degradation of Jack’s mental space Kubrick was so intent on inscribing in the movie, actually becomes seared into the serial character’s flesh. In this classic representational strategy of demonic invasion, the individual turns into both tormentor and victim. Just like preordained Fate for tragedy, the responsibility lies with the supernatural forces which trigger the character’s eventual disintegration in the show – and not so much with the character and his own choices. By deliberately transferring the reality of Evil back to some non-human power, Garris and King leave the door open for some potential redemption, a dimension Kubrick never contemplated in the film.

The Second Coming2

Jack’s entire being becomes the battleground of the fight between Good and Evil. Garris and Corso turn him into an entity visually and gradually cracking up under the demonic assault but fighting back for his own repossession in the final moments of his transformation. The type of visual pleasure formatted for the male gaze Laura Mulvey referred to in her famed 1975 essay “Visual pleasure and narrative cinema” is now geared toward horror film spectators and tailored for their normative expectations. Jack’s virtually tangible metamorphosis into a decomposing body and mind matches the recurring incursions of gory ghosts into the realistic diegesis. His encounter and wrestling with the dark side are spurred by the visions of long-deceased hotel employees and guests and have all the trappings of conventional horror. But by playing with textures and a chromatic range alternating between black and white and garish colors, cinematographer Shelly Johnson captures the characters’ fundamental displacement. Horror and more specifically fascination with body horror, whether intradiegetic or extradiegetic, takes center stage as the various planes of reality start intermingling and overflowing. Jack gets to witness his own horrific transformation experiencing firsthand the spectacle of horror. Turning into the monstrous object of his own scopic impulse adds yet another dimension to the central notion of trouble as he literally becomes a figure of the Other.

Fig. 12. Garris’s miniseries: Jack’s intense pain when undergoing his horrific transformation.

The experience of horror as spectacle is therefore mediated through his own eyes as well as the spectator’s. The act of violence on the audience witnessing such torture is hence first experienced at the intradiegetic level. In the vastly different context of the Vietnam War movie The Deer Hunter (Michael Cimino 1978), critic Vincent Canby comments on the hyperrealism of exploding brains or guts being turned into a highly theatrical spectacle by slow motion and garish colors. According to Canby, such “a spectacle [is meant] to elicit strong emotional responses” (Canby D23) and makes the viewer complicit. The very same tenet seems to apply in the miniseries. As “the archetype of the Bad Place […] which demands a historical context” (King, Danse Macabre 266-67), the hotel literally cannibalizes Jack who is in turn captured, being reincarnated into one of the hotel ghosts until his body eventually merges with the Overlook. The intense pleasure he feels at somehow becoming the locus horribilis is only mitigated by his own deep loathing of the Evil taking him over. Garris’s visual cues of his metamorphosis (greenish, decaying flesh, bloody eyes etc.) match the horror genre’s clichés, such monstrous rebirth and reincarnation materialize visual and mental distortion. But they also vicariously provide an in-depth exploration of the viewer’s sinister fascination with the contamination process at work.

Italian psychologist Franco De Masi points out that:

[the almost orgasmic-like pleasure of evil] involves an insatiable desire from which any respect for, or understanding of, the other’s need and existence is banished… The fascination of absolute, destructive domination of the helpless victim gives rise to a pleasure as stimulating and devastating as a drug. For this reason, the link between cruelty and mental ecstasy proves to be particularly dangerous. (De Masi 144-45).

In this anatomy of horror, Jack’s increasing signs of unease about his altered state are inversely proportional to the spectator’s pleasure. As he is both perpetrator and victim, he seesaws between embodiment of Evil and wounded victim so that his body bears the stigmata of this physical and psychological warfare. Such an alternation is congruent with the twentieth and twenty-first centuries’ treatment of the horrific. As Rick Altman underlines in Film/Genre, “With the horror film, a different syntax rapidly equates monstrosity not with the over-active nineteenth-century mind, but with an equally over-active twentieth-century body”. (Altman 224).

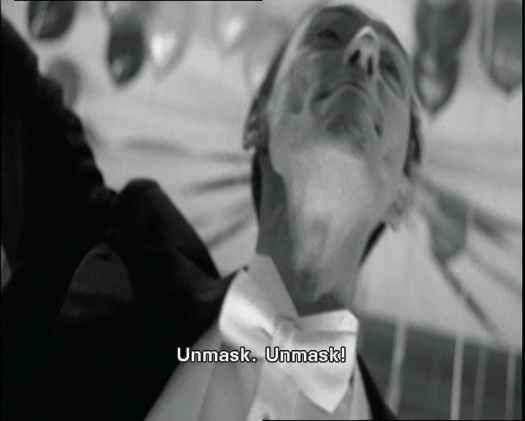

Fig. 13-14. The ghostly master of ceremonies trapped in the Overlook spacetime: playing on the chromatic range and the time dimensions

Fig. 14.

The miniseries’ alternation between black and white and color helps better expose the various layers of the characters’ eerie metamorphoses maximizing their impact on the viewer. The show’s spectacular pictorialization and play on textures, the materiality of decaying flesh and the framing of rotting faces for instance turn it into a kind of cinematic television. The black and white shot of the master of ceremonies ordering Jack and the guests to “unmask” artfully echoes Kubrick’s own black and white photographs of Jack and the hotel guests at the 4th of July ball at the end of the movie. The gap between what they were and what they are forever in the process of becoming is at the heart of Mick Garris’s mise-en-scene. He captures them in the course of turning into someone or something else, literally beside themselves. But if the disturbing revival of the various horrific figures contributes to showcasing their shifting natures, it’s also crudely exposed as an arrested development. Besides winning an Emmy for Outstanding Makeup, Garris’ show also garnered a Primetime Emmy Award for the Outstanding Limited Series category. In a famous 1983 Playboy interview, Stephen King kept insisting on the fact that The Shining was “about Jack Torrance’s gradual descent into madness through the malign influence of the Overlook. If the guy is nuts to begin with, then the entire tragedy of his downfall is wasted” (King in Norden, Playboy). The process of transformation successively captures the endless versions of Jack as obsession and loss of control take over. And Steven Weber’s “vaguely reptilian quality lurking in the contours of his face” (Meyer) further accentuates the scope of the mutation. The nightmarish images of the ghoulish masks simply render more palpable the characters’ shift to another plane of existence. Ironically, the original title of King’s horror novel Salem’s Lot, The Second Coming, functions as an inverted

reference to this new lease of demonic life and hellish reincarnation. Such an inversion of the Biblical motif of the Second Coming mimics and subverts the belief in the return of the Chosen One. W. B. Yeats’s 1919 poem of the same title also focuses on the end of an era after the first World War and the advent of world destruction. If Stephen King’s The Shining similarly chronicles the end and the horrific beginnings, it focuses on one individual rather than mankind at large and its collective rebirth. By inscribing the new excruciating reality of the main figure’s monstrous second awakening, Mick Garris delineates the contours of possession in a figure for whom “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold” (Yeats). The character’s progress toward the frozen center of the maze in Kubrick’s film morphs into a descending spiral in the series. The final parable of Jack allowing the boiler to explode in the hotel’s basement is a transparent metaphor for the Christian concept of the Harrowing of Hell and man’s descent into the Inferno. Stephen King’s use of Christian symbolism resurfaces even as it is reformatted for the singular purpose of exposing the downward trajectory of one single doomed individual. As Meyer also highlights:

It is interesting to note how Kubrick’s film ends with Jack Torrance lying dead in the snow, whereas Stephen King’s The Shining climaxes with Jack Torrance allowing the hotel’s boiler to overheat and explode. As King himself put it, ‘The book is hot, and the movie is cold. The book ends in fire, and the movie in ice.’ (Meyer).

So that just like the troubled hero’s, the characters’ journeys inside the hotel-world are all centred on the main themes of death and gruesome rebirth in both mediums. But King and Garris conjointly chose to reinstate the prevalence of space as a unique type of overpowering time-space unit. The ghostly hotel diversely materializes it, especially in the end sequence.

Fig. 15-16. Open ending: resurgence of the whole & recurrence in the miniseries. The ghostly Overlook rising from its (narrative) ashes (part 3)

Fig. 16.

The final shots of part 3 operate as a literal open ending. They inscribe on screen phantom images of the Overlook even though it has burned down. They also toy with the central notion of recurrence as the ghostly image of the burnt-down hotel magically rises once again. The essence of the specific Evil permeating the place is thus visually and narratively recycled thanks to the computer-generated optical illusion of the reconstruction. The contrast between the vivid colors of the park around the hotel in the foreground and on the sides and its faint, overexposed outline in the background seems to once again corroborate Mark Twain’s vision of History as a never-ending recurrence and offers yet another troubling visual clue of the persistence of Evil.

In a sense however, the same idea of endless cycle also inhabits Kubrick’s movie. The final close-up and photo inscribe two versions of a “frozen Jack.”

Fig. 17-18. The ironic twist on the Hollywood ending before the fade-out in Kubrick’s finale: Jack frozen in space and time

Fig. 18.

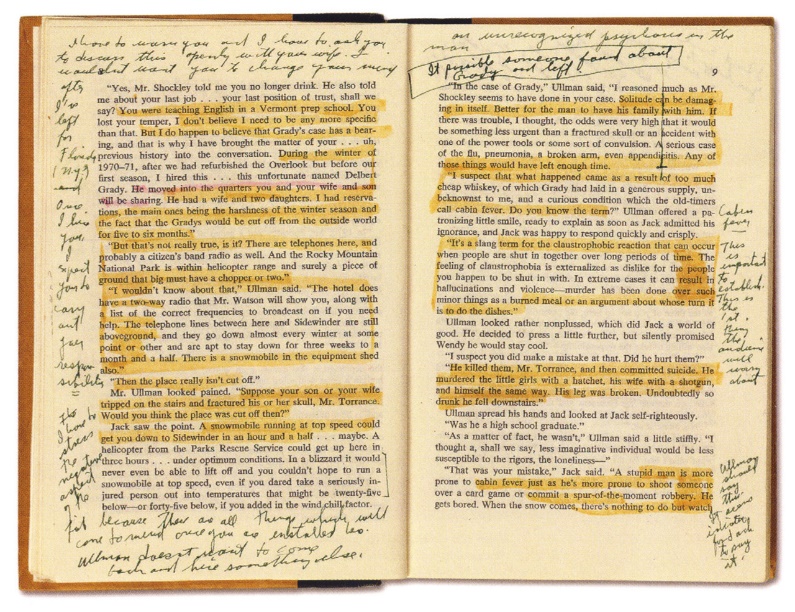

In the photograph at the end, as the reincarnation of a 1921 reveler, Jack smiles on forever in a continuum which at once erases the previous troubles and irretrievably harks back to them. The surreal depth of the picture frame substitutes for the horrific danse macabre of the maze but it also traps it in a timeless, always-there dimension which will forever tell the same past horror tale. The same principle as Roland Barthes’ photographic time and space paradox is at work here. As the frame eventually vanishes with the smooth zoom-in of John Alcott and Garrett Brown’s Steadicam, Jack is finally framed as the central piece in the entire ensemble, yet another displaced avatar mimicking the original and fitting in the hellish puzzle of the Overlook. The photographs on the Gold Room wall in the movie and the computerized generation of the Overlook silhouette in the teleplay are both there and not there, definitely breaking away from any previous sense of reality and narrative logic. They paradoxically foreground the notion of disturbance at play in the narrative and Jack’s irreducible otherness. Thus, in some perverse movement of recreation, the “troubles” are both immortalized and aesthetically smoothed over. What used to be there is shown forever reemerging amended through the filmmaker’s remedial lens. The final treatment of these images mirrors the corrective dimension of Stanley Kubrick’s overflowing notes in the margins of Stephen King’s copy of The Shining. The monstrous grafts not only reshape the palimpsest, they actually create a new authoritative one.

Fig. 19. Kubrick’s own version of creative work. Correcting the problems: overflowing notes in the margins of Kubrick’s copy of King’s The Shining.

In a matching counter effort, King in turn corrected Kubrick’s version in the 1997 teleplay and later his 2013 sequel Doctor Sleep, which Mike Flanagan adapted for the screen in 2019. Each new variation on the forms of horror further intensifies the sense of displacement and fundamental instability affecting beings, things but also viewers in the two mediums. The successive versions are all palimpsestic variations on the core horror of the source novel and the uncertainty born of their discrepancies compounds the deep sense of unease. Somehow, this series of derivatives and avatars enhances the intradiegetic clearance between the different adaptive realities of the filmic and serial narratives thus giving substance to what Linda Hutcheon calls “palimpsestuousness” in her 2006 book A Theory of Adaptation, “an adaptation is a derivation that is not derivative−a work that is second without being secondary. It’s its own palimpsestic thing” (Hutcheon, 9). And in such an iconic context, “palimpsestic” very much rhymes with endlessly “haunting.” In this sense, Mike Garris’ TV series bears the mark of the haunting of Kubrick’s own disruptive and unsettling version of the Overlook storyworld. The shift in paradigms has also been a shift in palimpsests which has radically displaced, and to some extent replaced, Stephen King’s source text and subsequent teleplay, partly preventing the series from existing on its own.