Born and based in Florence, Andrea Sirotti is a literary translator specialized in English and postcolonial literatures. Since the mid-1990s, he has edited and translated into Italian anthologies and poetic collections for various publishers by authors such as Emily Dickinson, Margaret Atwood, Carol Ann Duffy, Eavan Boland, Alexis Wright, and Arundhathi Subramaniam. Moreover, he has translated narrative texts by Lloyd Jones, Ginu Kamani, Hisham Matar, Hari Kunzru, Aatish Taseer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and Ian McGuire, introducing them to the Italian public for the first time1. With Shaul Bassi, he also co-edited the handbook Gli studi postcoloniali. Un’introduzione2.

In 2008, in collaboration with Gaetano Luigi Staffilano, Sirotti translated Alexis Wright’s novel Carpentaria into Italian, less than two years after the publication of the English original3. Published by Rizzoli, I cacciatori di stelle (“The Stars Catchers”) never achieved the expected commercial success: in fact, it was a sales flop, and for years the Italian translation of the novel has been almost unavailable on the market.

This retrospective interview with Margherita Zanoletti was conducted in Italian via an email exchange between 2021 and 2022, and subsequently translated into English by Zanoletti. In the meanwhile, Staffilano passed away at the beginning of 2022, making the project to communicate with him too, impossible4. The conversation with Sirotti revolves around the genesis and the outcome of the project of translating Carpentaria into Italian, offering close micro-readings of the novel as an exemplary instance of polyphonic writing. The discussion, structured in three sections (Part 1. The context; Part 2. Practical choices and textual examples; Part 3. Reflections), touches on the difficulties and the ethical and practical choices related to the translation process, the relationship between the author and the translators, and the editorial intervention of the Italian publisher, driven by commercial reasons – from the transformation of the title and the book cover design to the attempts to normalise Wright’s distinctly Indigenous Australian style. Through a series of memories and reflections looking back to an intense translation experience, and drawing on a number of relevant theorisations on translation theory and practice, including those by Antoine Berman, Lawrence Venuti, Peeter Torop, and Susan Petrilli, the interview also aims, on the one hand, to emphasise the twofold role of the author as a storyteller and spokesperson for the Indigenous minority and, on the other hand, to draw attention to the role of translators as readers, interpreters, mediators, and co-authors, offering some insights on the questionable dynamics of the publishing industry.

Part 1. The context

Margherita Zanoletti (MZ): Let us start from the very beginning. What was the genesis of the project of translating Carpentaria into Italian?

Andrea Sirotti (AS): It all started towards the end of 2007, when an editor of Rizzoli (a publishing house with which I had never worked before) contacted me, asking if I would be willing to participate as a co-translator in the Italian edition of what she described as “an Australian Aboriginal novel, a nice family story set in Queensland”. The reason why more than one translator was needed lay not so much ̶ as one might imagine ̶ in the difficulty of the text, but rather in the need to get the novel out in time for the Turin International Book Fair in May 2008. In fact, I remember that for the delivery, we would have had to respect the deadline of March 31, that is to say three months of work. Given the complexity of the novel, this was a decidedly tight time, even though there were two of us working on it, Gaetano Luigi Staffilano and myself. For various reasons, then, the publication process took longer than that, although it was not our responsibility.

I don’t know why they involved me. I had already had the experience of translating so-called ‘postcolonial’ fiction, and this might have played a role (although my other experiences in Downunder literature were limited, at the time, to the translation of Lloyd Jones’s Mr Pip5).

MZ: Most translation theorists agree that before embarking upon any translation the translator should engage in a preliminary stage involving analysis and research. This translation-oriented analysis should not only ensure correct interpretation of the source, but also “provide a reliable foundation for each and every decision which the translator has to make6”. In your case, where did you start from, before translating Carpentaria? How long did this propedaeutical phase take?

AS: As a rule, this preparatory phase should last a long time: the time necessary to become familiar with the cultural universe of the author and her story. I say it should, because this is not always possible. Before translating Carpentaria, in particular, I remember spending a few hectic days collecting as much material as possible about the author and the geographic and cultural context. The rest, alas, remained to be checked while the work progressed, especially when knowledge of specific characteristics became essential for the plausibility of the translation7.

MZ: Notwithstanding her international reputation, in Italy Alexis Wright appears to be still a niche name in the literary market. In term of wider notoriety, she has a long way to go8. How has your Italian translation of Carpentaria been received?

AS: A fundamental misunderstanding weighed on the reception of Carpentaria, I think. I always had the suspicion that Rizzoli had acquired the book in an attempt to repeat the success of some so-called ‘exotic’ novels released in previous years. One example is Khaled Hosseini’s popular novel The Kite Runner. In fact, among other things, I cacciatori di stelle apes the Italian title of Hosseini’s book, Il cacciatore di aquiloni (“The Kite Hunter9”) It is obvious that a reader who is buying a book titled I cacciatori di stelle, with a ‘nice’ cover and presented to bookstores as “a family story”, expects a completely different product from Carpentaria. This may explain, at least in part, the reasons for the novel’s limited sales. I have personally had feedback from friends who bought the book expecting to find certain “ingredients”, only to discover that it was instead a complex, ambitious book, and anything but easy to read10.

MZ: Australian literature still tends to be a small market in Italy, although in the new millennium, by and large, Australian literature has increasingly been recognised and positioned as a high-quality and innovative form of creative expression, just waiting to be fully discovered11. Do you think that your translation of Carpentaria contributed to Wright’s fame, and to the recognition of Australian Indigenous literature?

AS: No, I don’t. I think with regret that the Italian edition of the book has had very little impact in Italy, except perhaps in some academic circles who were ready and prepared to grasp and appreciate the scope and value of this literary work. In other words, it was a missed opportunity.

Part 2. Practical choices and textual examples

MZ: In Carpentaria, Alexis Wright’s storytelling is a stratified blend of myth and scripture, politics, and farce. In order to compose a sort of epic of an Indigenous people who is mostly illiterate, the author combines “English and Waanyi language, high and low diction, concrete and abstract elements, humorous and poetic expression, often in alliterative prose which sounds on the verge of scansion”. This way, Wright manages “to compose a wide-ranging epic novel, reminiscent of the songlines of her ancestors, but inscribed in an exogenous literary heritage in English, and written in a creative, hybrid style12”. This language is in stark contrast with the impoverished, colloquial English spoken by the local white community and the standard Australian English employed by the other white characters coming from different areas of the continent. What were the major challenges in translating this linguistic polyphony?

AS: Carpentaria is a novel that merges epic and everyday life and gives voice to three distinct communities residing in Desperance: two groups of rival Aborigines (living in the Westside and Eastside barracks respectively) gathered around their respective archetypal and charismatic ‘leaders’ (Norm Phantom and Joseph Midnight), and the community of whites living in the neat houses of Uptown. Despite appearances, in the novel the vulgar and materialistic inhabitants of Uptown, the people without history, although living in the respectable area of town are the real fringe dwellers. Their sterile respectability, narrow materialism, and racism which are at times violent, at other times paternalistic seem to be the real ‘capital sins’ in that world.

Not that the Aborigines are flawless and vice-free, far from it. However, the native characters always appear to us round, in a certain sense heroic: and if they fall, they do so grandly, like the epic protagonists. When you consider the structure of the novel in its wholeness, compared to the half-figure types of the white community, Norm Phantom, Mozzie Fishman, Will Phantom, and Angel Day stand out like giants.

Clearly, trying to recreate all this in Italian is quite problematic, also because one cannot run the always present risk of making a caricature of the Aborigines by employing a language full of solecisms or anacolutha. In contrast, the language of the white community can be made to sound more colloquial in various ways, even if it is apparently closer to the standard.

MZ: The issue that you raise recalls Lawrence Venuti’s widespread theorisation in The Translator’s Invisibility, where distinctions such as foreignisation/domestication, indicating opposite ethical attitudes, or resistancy/fluency, indicating corresponding discursive strategies, call the attention to the ‘politics’ of translation, which must balance commercial and literary imperatives13. In a foreignising translation, as proposed by Venuti, the translator intentionally disrupts the linguistic and genre expectations of the target language to mark the otherness of the translated texts. The scholar further argues that “discontinuities at the level of syntax, diction, or discourse allow the translation to be read as a translation […] showing where it departs from target language cultural values, domesticating a foreignizing translation by showing where it depends on them14”. However, as you observe, it is paramount to avoid the deforming tendency of exoticising and ridiculing the Foreign stressing the deviation from the morpho-syntactic standard15 From this perspective, could you provide a textual example taken from I cacciatori di stelle?

AS: As an example, let us take the incipit of Joseph Midnight’s long ‘tirade’, contained in the sixth chapter, which recalls the arrival of the chroniclers from the southern cities to Desperance:

Every day, never miss, the white city people started to metamorphose themselves up there in Desperance, and they were asking too many questions, millions maybe, of the white neighbours. Will Phantom was that popular. A big troublemaker but nobody had a photo of him. Got nothing to give, for the white people – too insular.

What they got to know? Got nothing. You could see they were city people who were too plain scared to go about, and come down there in the Pricklebush and ask the Aborigine people sitting at home in their rightful place. They looked, Oh! this side, or that side of town. No, not going, they must have said about the Pricklebush. Waiting and waiting instead. Those reporter types hung around town not knowing what to do, then they all looked outside of the fish and chip shop, and guess who? One old blackfella man, Joseph Midnight now, white hair jumping out everywhere from he head, he was sitting there. Him by himself: Uptown. He looked over his shoulder at those city newspaper people and saw they’d even got a Southern blackfella with them. A real smart one, educated, acting as a guide. He got on a tie, clean white shirt and a nice suit. He goes up to old man and called him, ‘Uncle,’ and he says: ‘What kind of person you reckon, older man, you say Will Phantom?’ Old Midnight he looked back for awhile, and he says: ‘Who’s this?’ He was thinking now for must be two minutes before he was squinty eyes, still saying nothing, and then he speaks back, ‘Well! You, you, say, I never, and I never believe it. You say I am your Uncle, then listen to this one, boy16. (Emphasis added)

Ogni giorno, immancabilmente, i bianchi di città cominciavano a metamorfizzarsi lassù a Desperance, e facevano troppe domande, forse milioni, ai paesani bianchi. Will Phantom era così popolare, ma nessuno aveva una foto di quel gran piantagrane. «Nulla da dare,» a bianchi come loro… che mentalità chiusa.

Cosa scoprirono? Nulla. Si vedeva che era gente di città che aveva una paura fottuta di andare in giro, di scendere nel Pricklebush a domandare alla gente ab origine seduta all’interno del loro legittimo posto. Guardavano, oh se guardavano! Da una parte, o dall’altra del paese. «Ma non ci andiamo» devono aver detto, intendendo nel Pricklebush. Lunghe attese, invece. Facce da cronisti che ciondolavano per la città senza sapere cosa fare. Poi guardarono tutti fuori dal negozio del fish and chips, e indovina un po’? Un vecchio blackfella, Joseph Midnight in persona, capelli che gli spuntano fuori dappertutto dalla testa sua di lui, era seduto là. Lui da solo: a Uptown. Guardò di sottecchi quei pennivendoli di città e vide che si erano portati dietro perfino un blackfella del sud. Uno intelligente, istruito, che faceva da guida. Aveva su la cravatta, una camicia bianca pulita e un bell’abito. Va dal vecchio e lo chiama «zio», poi gli fa: «Che tipo di persona mi dici che è Will Phantom?» Il vecchio Midnight lo squadra per un po’, poi dice: «E tu chi sei?» Ci pensa per un paio di minuti, poi strizza gli occhi, ancora senza dir nulla, alla fine gli fa: «Be’, tu… dici? Io non ci credo, mai e poi mai. Dici che sono tuo zio, allora ascoltami bene, ragazzo.17 (Emphasis added)

In the Italian translation, one can spot examples of high and solemn language mixed with specific idiolects. We have tried to recreate this expressive modality without elements that could involuntarily sound caricatured. Indeed, what we have attempted to restore is the Aborigines’ proud mastery of their own language. They make fun of anyone (white or subservient to Whites) who tries to water down or sweeten their expressions. Note, in bold, the mangled English adopted by the journalist to make himself understood better by the native elderly (“‘What kind of person you reckon, older man, you say Will Phantom?’”).

MZ: It should be noted that the reverse translation of “Che tipo di persona mi dici che è Will Phantom?” is “What kind of person do you tell me Will Phantom is?”. While the epithet “older man” has disappeared in the translation, the Italian pronoun “mi” (“to me”) is a strategic addition which immediately makes the sentence sound informal, almost childish. This, when combined with the anaphora of “che” mirroring the anaphora of “you”, plays a key role in transmitting the colloquial tone of the source, allowing it to be heard, though from a distance, by the receiving Italian audience18. This translation strategy contributes to preserve the polyphony of voices that characterizes Wright’s narrative, made up by a mixture of more formal language with idiomatic, colloquial expressions. Latinate vocabulary such as “metamorphose” and “insular” are emphasized by resorting to italicization (“metamorfizzarsi”) and punctuation (“…che mentalità chiusa”, in back translation “…what a closed mind”), while the derogative, archaic-sounding adjective “Aborigine”, also derived from Latin (“ab”, from; “origine”, origin) is turned into the Latin expression “ab origine” (“from the beginning”).

Clearly, instead of normalizing and flattening the language, you and Staffilano have preserved and even accentuated reference to the oral speech: yet the Foreign is never ridiculed. For example, the italicized sentence “Got nothing to give” is translated literally, as “nulla da dare”, between inverted commas; the choice of the poetic word “nulla” (“nothing”, from the Latin word “nulla”) instead of the more prosaic synonym “niente” contributes to evoke Wright’s “distinctive poetic qualities19”. The same change of punctuation, from italics to inverted commas, occurs with “No, not going”, translated as “ma non ci andiamo” (literally, “but we are not going there”), a sentence which intertextually refers to Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s famous poem “We Are Going20”. In other cases, shifts occur on a lexical and syntactical level. For example, in translation the syntagm “too plain scared” turns from colloquial speech to direct expression of vulgarity, as “avevano una paura fottuta” means, in reverse translation, “were scared shitless”; emphasised by Wright through the use of italics, the alliteration “from he head” (a grammatical variance of “his”, where the personal pronoun “he” is employed with an adjectival function) is translated into the redundant expression “dalla testa sua di lui”, where “sua” and “di lui” express the same meaning (both mean “his”; in back translation: “from his head”); while the informal phrase “He got on a tie” is echoed in the Italian translation “Aveva su la cravatta” (literally, “He had his tie on”), as the phrasal verb employed “avere su” (“to wear”, “to have on”) sounds far more colloquial than the prepositionless verb “avere” (“to wear”, “to have”). Similarly, spoken words that have been transcribed in the source are perpetuated in the translation. For example, “One old blackfella man” (without italics in Wright’s text, as the word “blackfella”, a variant spelling of “blackfellow”, has been lexicalised in English) is only partially translated as “un vecchio blackfella” (“an old blackfellow”). The term “blackfella” is italicised thus made more visible to the eyes of readers. While the omission does not interfere with the function of the text, the cultural reference is left on the page, leaving the reader to recover its meaning from the context.21

Reciprocated in the Italian translation, Wright’s intermingling of languages, registers and references provides an Indigenous worldview in writing. Wright sets her novel in the area around the Gulf of Carpentaria in northwest Queensland, which is the home of her people: the Waanyi. She draws not only on the dramatic topography of the region, but on an essentially non-European vision of humankind’s place in the world. Could you comment upon this aspect?

AS: Wright’s world is visionary and concrete at the same time. Local facts and rumours coexist with the legends of the Dreaming; ancestral myths and sacred stories are treated with a matter of fact and sometimes tragicomic tone in a very original and paradoxical language, which is sublime and quotidian, traditional, and innovative at once. This mixture certainly sounds like a rather unheard-of blend. This novel, therefore, also delights in daring linguistic research, in the continuous juxtaposition of points of view, in the occurrence of sections that can be definitely classified as ‘interior monologues’, in search of a language (especially the English used by the Indigenous protagonists) that sounds native and foreign, colloquial, and solemn, everyday and epic at the same time, with an idiosyncratic use of some ‘highbrow’ terms. It appears as if the author was particularly interested in the literary and intellectual definition of a communicative code useful for colonising the language of the colonizers by pushing it to the extreme (as in Rushdie’s famous formula “the Empire writes back22”).

MZ: Wright’s novel teems with extraordinary characters: from the rulers of the family, the queen of the rubbish-dump Angel Day and the king of time Normal Phantom, to Elias Smith, Mozzie Fishman, Bruiser, Captain Nicoli Finn, and Will Phantom. What character did you end up empathizing most with?

AS: Among the characters, I remember being very impressed by Elias, the man arrived from the sea “who had his memory stolen”. (C, p. 42) Despite being white, he is an outsider, one who collapses just when he compromises with the whites. His role, however, remains (somewhat) central even after he dies, with Will first and then Norm caring for and talking to his mummified corpse.

MZ: What page or episode would you pick and recall as the most moving?

AS: Among the most intense pages of the novel, I would mention the episode in which Angel Day, Norm’s indomitable, sensual, and individualistic wife, the one who builds the necessary and the superfluous by recycling the waste of the whites, discovers a statue of the Virgin Mary in the landfill and then repaints it in her own image and likeness, just like an ordinary woman from Pricklebush. This episode is a postcolonial reinterpretation of the religion of the oppressors:

The Virgin Mary was dressed in a white-painted gown and blue cloak. Her right hand was raised, offering a permanent blessing, while her left hand held gold-coloured rosary beads. Angel Day was breathless. ‘This is mine,’ she whispered, disbelieving the luck of her ordinary morning.

“This is mine,” she repeated her claim loudly to the assembled seagulls waiting around the oleanders. She knew she could not leave this behind either, otherwise someone else would get it, and now she had to carry the statue home, for she knew that with the Virgin Mary in pride of place, nobody would be able to interfere with the power of the blessings it would bestow on her home. “Luck was going to change for sure, from this moment onwards,” she told the seagulls, because she, Mrs Angel Day, now owned the luck of the white people.

[...] This was how white people had become rich by saving up enough money, so they could look down on others, by keeping statues of their holy ones in their homes. Their spiritual ancestors would perform miracles if they saw how hard some people were praying all the time, and for this kind of devotion, reward them with money. Blessed with the prophecy of richness, money befalls them, and that was the reason why they owned all the businesses in town.

The seagulls, lifting off all over the dump, in the mind-bending sounds they made seemed to be singing a hymn, Glory! Glory, Magnificat. (pp. 22-23)

La Vergine aveva una veste dipinta di bianco e un mantello azzurro. Teneva la mano destra alzata in perpetua benedizione, e con la sinistra reggeva un rosario dai grani dorati. Angel Day rimase senza fiato. «È mia», sussurrò, incredula di quanta fortuna le fosse capitata in quella mattina qualunque.

«È mia», ripeté a voce alta al gruppo dei gabbiani in attesa attorno ai resti delle siepi di oleandro. Sapeva benissimo di non poter lasciare lì la statua, altrimenti l’avrebbe presa qualcun altro, e di doverla portare a casa, perché era certa che, con la Madonna a proteggere il luogo, la sua casa e la sua famiglia sarebbero state protette da benedizioni potentissime. «D’ora in avanti la sorte cambierà di sicuro,» disse ai gabbiani, perché lei, la signora Angel Day, adesso possedeva la stessa fortuna dei bianchi.

[...] I bianchi si erano arricchiti mettendo da parte abbastanza soldi da poter guardare gli altri dall’alto in basso, proprio perché tenevano in casa le statue dei loro santi. I loro progenitori spirituali avrebbero fatto miracoli ascoltando tutte quelle preghiere, e avrebbero ricompensato una simile devozione in moneta sonante. Benedetti dalla profezia della ricchezza, il denaro pioveva loro addosso ed era per questo che gestivano tutte le imprese in città.

Sembrò che i gabbiani che svolazzavano sulla discarica avessero unito le loro grida penetranti per intonare un inno: «Gloria! Gloria, Magnificat23!»

MZ: In this passage, as you observe, the lexicon of Christianity is translated into Indigenous knowledge. Spiritual, real, and imagined worlds coexist. Just like in the previous example, here too the Italian translators, though aiming at communicating with readers with limited awareness of Indigenous issues, avoid the temptation of domesticating the source. The excerpt features many references to the Christian spirituality, which in most cases the Italian translation renders literally. Words like “blessing” (“benedizione”), “rosary” (“rosario”), “miracles” (“miracoli”), “devotion” (“devozione”), and the Latin-injected hymn “Glory! Glory, Magnificat” (“Gloria! Gloria, Magnificat!”) are cultural borrowings from the Western world, which find direct correspondence in Italian. What does not have an equivalent is the Aboriginal world vision. The overlapping of past, present and future imbuing the prediction “Luck was going to change for sure, from this moment onwards” is translated into the Simple-Future sentence “D’ora in avanti la sorte cambierà di sicuro” (reverse translation is “from now on, luck will certainly change”). Clearly, Angel Day’s perspective is in striking contrast with the linear conception of time of the average Italian reader. Her viewpoint is that of an Indigenous woman, for whom “all time is intertwined, important and unresolved as Aboriginal people see the time immemorial in our culture24”, and the Italian translation cannot mimic Angel Day’s mixture of tenses, as it would sound like a mockery. In contrast, the sentence “she told the seagulls, because she, Mrs Angel Day, now owned the luck of the white people” expresses hybrid temporality in the Italian translation too: “disse ai gabbiani, perché lei, la signora Angel Day, adesso possedeva la stessa fortuna dei Bianchi” (in back translation: “she told the seagulls, because she, Mrs Angel Day, now owned the same luck as the Whites”). Notably, the capitalisation of the word “Bianchi”, introduced in the translation, appears loaded with irony, preserving Wright’s humorous tone.

As the comparative reading of source and translation suggests, the challenge for the translators is not limited to the linguistic level but includes intercultural issues, as “the source-language word may express a concept which is totally unknown in the target culture. [ …] Such concepts are often referred to as ‘culture-specific25’.” The translator acts as a cultural mediator, who interprets and expresses stories and themes that are limitedly known by readers outside the Australian context.

From this perspective, literary translation is always a political act. The texts that are selected to be translated ultimately shape the literary market and intercultural relations and, as Mikhail Bakhtin suggested in his discussions of dialogism and heteroglossia, the ways in which a work is translated ineluctably reflect and express an interpretation of the source and a (semio)ethical stance26. Can you suggest the main political, hermeneutical, and ethical issues raised by the process of translating Carpentaria?

AS: Translating Carpentaria entails ethical problems, as Wright published it as a reference text for a denied nation and their language. In a recent retrospective article for the Guardian, she wrote:

One of the most frequent questions authors are asked is, “Who are you writing for?” The audience I had in my mind while writing Carpentaria was the ancestors of our traditional country. I concentrated on the way our people speak to country and each other. In that way, it always felt as though I was writing a story to the old people about the complexities and bravery of our world today but also, by linking the past and the present in this way, I was bringing the ancestral realm into a story of all times27.

At the time, we did not know all this. We learnt it later, in the course of work. However, from the first pages of the book, Staffilano and I understood that what we had been entrusted with was an important novel, which required radical and courageous choices. At the same time, we were aware that the leeway we had was not unlimited. That is to say that we had to accept some compromises.

MZ: How did this awareness reflect in your translation, in practical terms?

AS: In our translation, I think I can say that in general we managed not to flatten Alexis Wright’s style, keeping the paradoxical and mock-epic tone, and respecting the linguistic registers and the lyrical qualities. In some cases, we accepted the editorial staff’s proposal to streamline the adjectives and cut down on anaphors28, but apart from this, I believe that our translation does a good service to the author and to the work.

MZ: How did you translate the realia29 featuring in Carpentaria?

AS: Rizzoli’s editorial staff invited us to have some Aboriginal terms translated or explained in the text. Called on by myself to settle the question, Alexis Wright was succinct about it. She pointed out that the Aboriginal language words and sentences in the original Australian and UK publication did not include any translation. Therefore, for consistency, in her opinion the Rizzoli publication should have been the same. The Aboriginal language should remain in the text30.

Staffilano and I agreed upon a univocal way to translate the hydro-geo-morphological and cultural characteristics of the territory, leaving many of the most recurrent terms untranslated, such as “claypan” / “saltpan”, “bush”, “Pricklebush”, “Blackfella”, “Outback”, “Abo”. In a number of cases, we chose to leave the original word in italics and to insert an explanation in the text.

MZ: Venuti criticises domestication as a site of racism and violence. For the scholar, domesticated translations “conform to dominant culture values”, while foreignisation or resistancy “challenges the dominant aesthetic” as new ideas, genres and cultural values are welcomed31. Did the editorial staff attempt to domesticate, or normalise Wright’s distinctly Indigenous style? Was it necessary to ‘protect’ your translation?

AS: Several times we had to hold back their attempts at standardisation and appeals to ‘accessibility’ and ‘readability’. It was not so obvious to make it clear that reading difficulties were an integral part of the stylistic choices of the author, to whom we felt we must be faithful.

MZ: As a translator, do you employ footnotes, introductions, appendixes, glossaries to make it easier for readers? Why are these apparatuses absent in the Italian edition of Carpentaria32?

AS: I often make use of endnotes, glossaries, and appendices to clarify some aspects of the text without the apparatuses interfering too much in the fluidity of reading. Especially when it comes to translating postcolonial poetry, inserting these paratexts seems useful and necessary to me. In the case of Carpentaria, however, we were told that the notes would not be included.

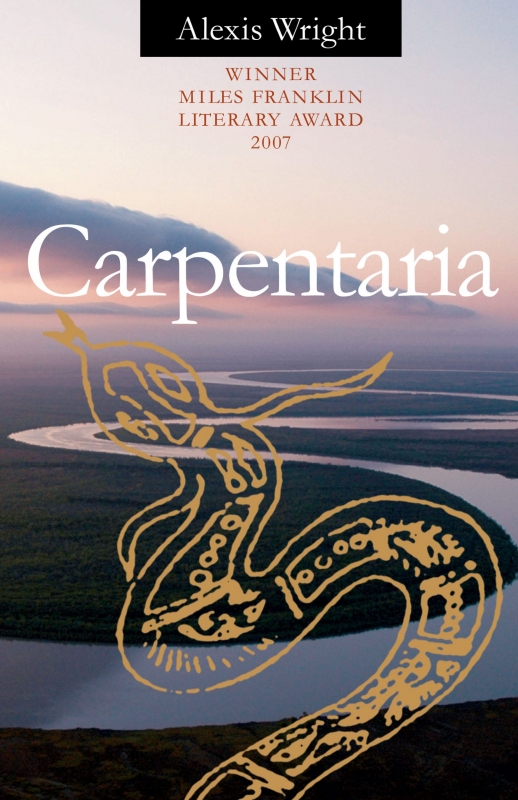

MZ: Still on a paratextual level, were the transformation of the title from Carpentaria to I cacciatori di stelle and the book cover design your choices, or the publisher’s preferences? Also the typographical variations at the beginning of chapters in the 2006 edition were erased in Italian. Were these changes driven by commercial, aesthetic, or communicative reasons?

Fig. 1. Alexis Wright, I cacciatori di stelle [trans. Andrea Sirotti and G. L. Staffilano], Milan, Rizzoli, 2008. Book cover.

By kind permission of the publisher

Fig. 2. Alexis Wright, Carpentaria, Artamon NSW, Giramondo Publishing, 2006. Book cover.

By kind permission of the publisher

AS: None of the changes that you mention were made by the translators (in fact, this rarely happens), but by the publisher, and in particular its sales department or marketing consultants33. It would not have been particularly difficult, for instance, to reproduce the original title without changes, which by the way sounds like an Italian word! The contrast between the two covers is even more puzzling. In the Italian book an idyllic and harmonious tropical environment is depicted, while the original cover could be seen as disturbing: the ‘ancestral snake’ stands against the background of an inhospitable landscape. They seem to be two completely different, almost antithetical books34. I remember that the author, whom I was lucky enough to meet twice in the spring of 2009 during her Italian tour after the publication of the novel (first at the “Incroci di civiltà” festival, in Venice, then at Monash University in Prato), admitted that she was rather upset by the publisher’s choices. As for the poetic parts all in capital letters at the beginning of the first two chapters35, we translators had respected the original intention. Evidently the final choice was not to keep them. But the reason is unclear to me.

MZ: How did you collaborate with Staffilano, in practical terms? Did you translate together all chapters? Did one translator write the first draft and the other translator do the revision?

AS: After having discussed the translation approach and the fundamental choices, we divided the chapters up and began drafting. Then, we scrupulously revised each other’s work trying to harmonise the style, employing the word search function to standardise the translation of key concepts.

MZ: In a recent interview, you declared: “In my experience, being in touch with the authors (by e-mail, Skype or, in some lucky cases, even in person) has often been fertile and enriching. As is, generally, the dialogue and exchange with the reviser appointed by the publishing house, especially if she is also a translator and therefore someone able to fully grasp the difficulties of the job and the characteristics of the style to be reproduced36.” How did this work out, in the case of Carpentaria?

AS: I must say that deadlines were too tight for Staffilano and I to be able to have a fertile conversation with the author while the project was ‘in progress’. It was only towards the conclusion that we submitted her two lists of questions. We forwarded her the first list through the editorial staff (in some cases, publishers prefer not to provide translators with the private contacts of authors, and act as an intermediary for them), while ̶ once the urgency had been acknowledged ̶ we sent her the second list directly. Wright was very willing to collaborate. She was happy that her work was being translated into Italian and curious to ‘hear’ the results. She said she was amazed that Carpentaria was being translated into our language. She couldn’t wait to see the finished book37.

MZ: Did you involve other people during the translation process? And which technological tools did you employ?

AS: Apart from Staffilano and myself (and the editor), no other person was directly involved in the translation. It is true, however, that during the work I often consulted with my American friend and translator Johanna Bishop (I often ask the opinion of English-speaking colleagues for my translations). With her I discussed some controversial parts or some specific terms in context, to understand how they resonated with a native speaker. The first and eighth chapters, I remember, were subsequently analysed during a couple of my Master’s degree classes in Postcolonial Translation at the University of Pisa. As for the technological tools, we used nothing else but some online dictionaries (including one of Australian English) and a speech synthesis software for reading. At the time, a handy open-source program called Read please was quite popular. Today, as we know, everything is simpler, as the text-to-speech plugin WordTalk is incorporated in Microsoft Word.

Part 3. Reflections

MZ: Translators are readers, interpreters, mediators, co-authors. What definition in your opinion best describes the act of translating?

AS: On a case-by-case basis, translators can play each of these roles (and others as well). I like to think of translators above all as very attentive readers, who do research, ask themselves questions, do not give in to the superficiality or laziness of a first impression. Only in this way can the translation be based on the interpretation process that is essential to establish that relationship of understanding and empathy necessary to be faithful to the source text.

MZ: In a past interview you observed that “translating is a way of returning home, richer, after the long journey through the text38.” How did the experience of translating Carpentaria enrich you? Do you think that the translator and the reader travel the same distance?

AS: Whenever I lecture on translation, Carpentaria figures among the examples I cite more often. It is the classic case of a work, as I like to say, “translated by difference39”. Due to various circumstances two European white men, with more or less stable life habits, find themselves translating the work of an Indigenous woman from the other side of the world. Precisely because the differences are so marked, a lot of humility is needed. We need to listen and try to abandon as much as possible the reassuring mental framework of our everyday life and profession, which allow us to translate culturally-related works ‘on autopilot’. The journey, therefore, is long and full of rewards: for both the reader and the translator. We return home enriched because we have learned to let experiences and points of view that we never even imagined existed resonate within us. This way we discover, perhaps, that these experiences and points of view are closer than we imagined to our way of feeling.

MZ: In the Afterword of your Italian translation of Emily Dickinson’s poems, you write that yours is “a translation that aspires to be the bringer of fidelity40”. In translating Carpentaria, what are the dominant41 characteristics of Wright’s poetics you have aimed to be faithful to?

AS: Certainly, the literary tension of the language, its solemnity and, at times, lyricism are dominant. Many were the moments when it seemed to me to translate poetry due to the author’s particular attention to aspects such as rhythm, sonority, and prosody. The stories of the protagonists are always told in a hyperbolic and “larger than life” style. A bizarre, paradoxical, extravagant, excessive, and absolutely unpredictable style. The translator must try to recreate all this and, as is evident, this sits at the antipodes (not only the geographic, but also the translation antipodes) with respect to a domesticating or normalising translation.

MZ: In recent years, translation scholars have become increasingly interested in the role of emotion in the translation process and in how it impacts on translation performance42. In your experience, did the process of translating Carpentaria entail an emotional involvement? What role did your emotions play, in translating the novel?

AS: It is difficult for me to answer this question many years later. Even re-reading parts of the book today, I cannot honestly recall the emotions that I felt during the reading and translation. I can say that at the time I was very much in agreement with what the Australian anthropologist Nonie Sharp had said commenting on the novel:

Why does this book move me deeply? Because it stirs up feeling on how one might live in tune with the ecology of place, the cycles of the cosmos? A parable about how, if we don’t live in this way, nature and her beings – ‘the elements’ – make retribution? James Lovelock and other world scientists see this in their own way: as The Revenge of Gaia. But for them too an elemental sense of being stirs at this late moment of history. Upon this larger canvas Carpentaria, a work of magic realism in Westerners’ language, becomes a powerful allegory for our times: the Earth’s retaliation in Gaia-like fashion, responding to the deep tramping marks of our footprints on the climate, on the places of both land and water.43

This is such a relevant comment today, in the so-called “Anthropocene”, just as the novel we are talking about is relevant in many respects.

MZ: You are not only a translator, but also an English teacher. How do these two activities connect? Have you ever employed Carpentaria for didactic purposes?

AS: Working as a high school teacher, I have often employed the texts that I was translating in my literature or translation classes. Students get generally very curious about stories from distant and unknown places. I have frequently taken them with me on an imaginary ‘voyage’ to the India of contemporary Anglophone poets, to Chimamanda Adichie’s Nigeria, Hisham Matar’s Libya, or the Bougainville Island of that splendid Dickensian rewriting that is Lloyd Jones’s Mr Pip. With Carpentaria I hesitated, perhaps because the English language employed by Alexis Wright is a bit too literary and complex to read without too much hermeneutic efforts at the high school level. Masters and translation schools are a different matter. At university level, Wright’s novel is an almost inexhaustible source of didactic examples.

MZ: As a final question, let us think in intersemiotic terms. What else, in your opinion, could (your translation of) Carpentaria be successfully translated into? A film? A musical work? A poem? A cycle of paintings? A website? A literary remake? A graphic novel? A videogame?

AS: Yours are all interesting suggestions. However, the hypothesis that comes most naturally to me is the film adaptation (or perhaps a TV series) that takes its cue from the novel’s narrative and protagonists. The visual and cinematic potential of the book is evident, even if, overall, Carpentaria is more a novel of words than images, and any adaptation that did not take this aspect into account would inevitably lead to an oversimplification.

I am also curious about the hypothesis of a musical, or perhaps a concept, as they once used to say, based on Carpentaria’s story and characters. Who knows if anyone in Australia or elsewhere has thought or is thinking about it? In fact, there is a lot of music in this novel. Classical music, Handel above all, but also the incongruous and paradoxical presence of a warbling Italian tenor (a miner) who sings “ma per fortuna è una notte di luna” (“but luckily it’s a moonlit night”, from Giacomo Puccini’s Bohème) in that remote land. And country and western music: the constant soundtrack of the caravan of the religious zealot Mozzie Fishman. These genres are reinvented and made almost unrecognisable by Wright, as in this context other cultural elements are reinvented and redesigned.

Conclusion

Since the beginning of this project, the primary goal of interviewing Sirotti has been to offer a first-hand, tangible testimony of the translator’s work, accounting for the interpretive path entailed by the process of translating Carpentaria into Italian. Through this interactive dialogue, conducted from a distance, the translator looks back to his experience and reflects retrospectively on its political, hermeneutical, and ethical implications, allowing his work to be finally “visible”. In this respect, the interview proves to be a powerful methodological tool to disclose and historicise key contextual information related to the publication of Wright’s novel in Italian, which otherwise would have remained hidden.

However, an attentive reading reveals that the conversation with Sirotti goes beyond a mere recollection of a past translation experience, highlighting at least two potential new directions and approaches for translation focused research.

The first significant aspect is that, as the case study at the heart of the interview shows with particular evidence, the politics of translation must balance commercial and literary imperatives, notably in the case of works from minority and postcolonial authors such as Alexis Wright. Reconstructing these background dynamics is essential to better understand not only how and why a translation was published, but also how and why a literary work, especially if belonging to a ‘minor’ literature, is accepted within and connects with a receiving cultural system44.

This issue clearly emerges when considering the contrast between the translation approach of the publisher and that of the translators. On the one hand, Rizzoli’s requests towards a translation as “domesticated” as possible, devoid of footnotes, translators’ notes, and other critical apparatuses that would make the translators’ work more evident, as well as the transformation of the original title Carpentaria, perhaps considered too cryptic, into the more “marketable” I cacciatori di stelle, can be seen as commercial strategies to present Wright’s work to potential readers as a political-free, pleasant to read, and exotic novel. The tight deadline allowed for completing such a complex task as translating Carpentaria into Italian, imposed by the publisher, was also dictated by commercial needs. On the other hand, Sirotti and Staffilano’s foreignising translation move in an entirely different direction. As the micro-readings offered in the interview display, although the translators admittedly had to “accept some compromises”, they did not conform to the readers’ expectations simplifying Wright’s stratified language, but rather preserved the stylistic uniqueness of the original as much as possible. Their attempt was to mediate between their tendency towards ‘resistive’ translation and the need of the publisher for fluency and stylistic standardisation. This approach, which goes against the current mainstream of Italy’s publishing market45, reflects their ethical intent to let the Foreign shine through, allowing the reader access to a multidimensional story made of a polyphony of voices.

Observing these dynamics, we can gain a deeper understanding of why until now the Italian market has not been able to fully appreciate I cacciatori di stelle. As it is translated, the novel represents neither of the two “extremes” that so far have found the favor of the Italian public: the “exotic”, namely, what is seen abroad as “Australian” in stereotypical terms (for instance, novels set in Australia, Australian blockbusters, etc.), and the “domesticated”, namely, what is easy to sell (for example, genre fiction46).

A second relevant point that the interview raises is that any literary translation, including the translation of a “minor” literary work, always moves also on a multimodal and intersemiotic level. In other words, in order to achieve a thorough assessment of a translated work, analysing the linguistic aspects only is not enough. Rather, it is paramount to go beyond a verbocentric approach and consider the material and nonverbal elements too47. While, for instance, within translation studies, only a few writings in English deal mainly or exclusively with covers of translations48, the book cover, the page layout, the choice of paper, and the typographical elements should be all considered as aspects which jointly contribute towards a “resistant” or a “domesticated” translation. For example, the paratextual transformations introduced by the publisher Rizzoli, and in particular the makeover of the original book cover into a different design, cannot be considered as a merely accessorial element but an integral part of a multimedial translation process. As a matter of fact, the resemiotisation of the original cover illustration into a ‘pleasant’ landscape design ends up communicating to potential readers an idea of Carpentaria which does not entirely reflect the literary features of Wright’s work.

Considering these two aspects, the Italian translation of Carpentaria stands out as an exemplary case of “minor literature” in translation, where the interconnected roles of translators, authors, editors, designers, and publishers still wait to be fully acknowledged and investigated. In this respect, interviewing Sirotti has programmatically aimed, on the one hand, to contribute to make the translators’ work more visible, “inviting a critical appreciation of its cultural political function and a reexamination of the inferior status it is currently assigned in law, in publishing, in education49”, and on the other hand, to stimulate further reflection upon current understandings of ‘visibility’ across translation theory and practice.

![Fig. 1. Alexis Wright, I cacciatori di stelle [trans. Andrea Sirotti and G. L. Staffilano], Milan, Rizzoli, 2008. Book cover.](docannexe/image/876/img-1-small800.jpg)