On the threshold of fine arts practices, embroidery is one of the techniques that belongs to the greater area of textile arts and has gained prominence since the avant-garde movement and the Second Wave feminism from the 1960s. Embroidery and stitching have been explored in Brazilian contemporary art and editorial production as an ethos of an ambivalent aesthetics that recalls a feminine poetic imagery in which the materiality of fabric and thread is recovered as a sign of skill, persistence, affect, and memory. There is some level of indecisiveness in this intermedial aesthetic practice because it swings between craft and art, image and text, artist’s book and illustrated book. Our discussion in this work revolves around the intermedial works of the Brazilian visual artist Julia Panadés1 in her use of embroidery and stitching to illustrate the poetic prose Névoa e Assobio (2017) by Bianca Dias2.

In Névoa e Assobio, the poetic narrative of a mother recalls the painful neonatal loss of Caetano. It is a volume illustrated by the visual artist Julia Panadés using embroidery and stitches as emblems of surgical sutures in search of psychological healing.

The illustrations are constituted by a threaded materiality that enables the juxtaposition of word and image that function both as illustration and a register of memory. As paratextual elements of these books, they enact themselves as intermedial references and as intermedial transpositions, in terms of Irina Rajewsky’s semiotic categories3, at the same time their illustrative function unfolds as iconotexts, according to Liliane Louvel4 (2006). Therefore, this paper means to reflect upon the intermedial role of embroidery and stitching as illustration in literary production to bring forth discussions on materiality (Gumbrecht5) and the interplay between image, text, and touch. Threaded illustrations unfold deeper meanings, such as a search for psychological healing and the imprinting of memory.

Materiality and memory

An embroidered cloth recalls the ancestral act of registering our thoughts by piercing a surface to retain symbols. It returns to the textural nature of writing and the first formats of the book. Alberto Manguel6 reminds us that one of the primeval media to record symbols were the clay planks, where humans could scratch their surface and later put them together to form a “book”. In this way, the meaning of text and textiles share the same root from the Latim, texere, an inflection of texō, pointing to an act of construction and weaving in such a way that when we write, we are weaving complex layers of meaning.

Embroidery in contemporary art has been recognized as a gesture of repetition, rhythm, and movement that requires craftsmanship and discipline. It has the potential of putting color to shapes, drawing patterns, letters, and texturizing surfaces with the subtle tri-dimensional effect such as embossing. It is not less complex than weaving, for it requires planning, color harmony, discipline, and endurance. The needle perforates the fabric countless times, and the colored threads fill in the space. Its execution is laborious but rewarding. However, it has not received much theoretical attention in comparison to weaving. The German American Bauhaus artist and textile master, Anni Albers7, demonstrated her profound preference for weaving and textile design. For her, the structure of a fabric is characterized by its constructive nature. Embroidery, on the other hand, is decorative surface work, according to Albers8, for it is does not demand elaborate thinking on its engineering, on its act of building up a structure.

Even though embroidery may have been underestimated by designers and experts for its decorative function, it is a mediatic cultural product. Jacques Rancière in Le partage du sensible9 contests the hierarchy among the arts and its theorization. He further defends an egalitarian treatment for the arts, and between the images and the signs over surfaces as a political act. In this way, everyone would have access to aesthetic sensibility because in this theory of art, the artistic sense is a mode of articulation in consonance to the ways things are done, their forms of visibility, and the way their conceptualization is elaborated. In this way, artistic sensibility can be shared democratically, not only among academics or experts.

In this spirit, I return to Anni Albers who pointed out to textiles as a medium that responds to the sense of touch, just as colors respond to vision. According to her, we need a receptive mind to discover meaning in the language of color. However, it takes an acute sensitivity to access a tactile language to unveil the meanings of its materiality. Given the appeal to visuality and to tactility found in embroidery, this study was based on the notion of media as proposed by Claus Clüver10, who states that artistic material are the media of the artist, and by Lars Elleström11 (2021) who understands that any material with a communicative function is a media product and who also conceive media as communicative tools constituted by inter-relational resources and modalities.

The interplay between image and text in the works under analysis here are merged in such a way that they constitute an iconotext, or the attempt to put together image and text in fusion, bringing to life a new object, in this case, illustrated books, according to the studies of Liliane Louvel12 (2011). The approach to embroidered illustrations as media of sensory and material modalities were developed in my previous studies13 (VIEIRA, 2020; 2021). The intermedial phenomenon involved between text and textiles are varied, but here we deal mainly with the notion of intermedial references by Irina Rajewsky’s (2005). My preference to work with the theoretical field of intermedia can be justified by the constitutive material qualities and modalities of the media involved, which corresponds to the extra-diegetic qualities of the text, its visual-tactile modes in relation to the verbal dimension of literary texts in a mirroring interplay.

The presence of an absence

Névoa e Assobio was published in 2017 in Brazil, and it recalls the sensitive issue of a neonatal loss in a poetic narrative of mourning with affection and tenderness. The text is by Bianca Dias whereas the illustrations are attributed to Julia Panadés. The volume surprises by the gentleness with which it combines the verbal text with a visual modality that evokes the tactile sensibility through sewing and embroidery. Weaving and writing restore meaning to the chaos of loss and become emblems of a desire for regeneration. Sewing and embroidery are interwoven by the verbal textuality that grant a double meaning to the work of Dias and Panadés: that of writing and sewing as restorative activities.

The volume’s poetic density presents us with promising investigative paths, but the focus of this analysis will rely mainly on the poetic affinities that intertwine textile arts and contemporary Brazilian literature. The intermedia relations that are manifested in the volume characterizes an iconotext as described by Lilliane Louvel14 (2006, 2010) due to the integration of word and image configured in the articulation between the text of Dias and the visual work of Panadés that happen in co-presence.

To begin with, the poetic genre of the volume is not easily discerning. The narrative is about a poignant pain, and we do not know if it is an autobiography, a diary, a narrative poem or even a narrative fiction. In addition to this rupture to the compartmentalization of poetic genres, the text-image relationship also generates undefinitions: after all, is it an artist’s book, an illustrated book, or a book of illustrations with poems? The verbal text merges with the visual work in such a way that the voices of Dias and Panadés are juxtaposed in constant crossing. Julia Panadés’ creative process is meant to be inspired by the text to create her works, however she often merges with it. This visceral involvement is evident in Névoa e Assobio, so that intermediality participates as a key concept of this poetical-aesthetic gesture of this work. As a work that inhabits the thresholds and given its unclassifiable features, the notion of intermediality as proposed by Clüver, Rajewsky and Lars Ellestöm elucidate the hybrid quality of Dias’ œuvre.

In this way, mediality play an indispensable role. Firstly, the iconicity of the illustrations presents themselves as an aspect impossible to ignore in the textual composition when using not only traditional visual techniques of the visual arts, such as watercolor and dry pastel sanguine, but also sewing on paper. The visual influence of the artist Louise Bourgeois is configured as a propeller of the gesture and the aesthetics of the visual elements, especially if we recover the work Ode à l’Oubli [Ode to Oblivion] (2002). Such influence is quite evident for the predominance of the bloody red hue and in the forms that constitute Panadés’ trilogy alongside the volume: Pregnant Woman, Fertile Woman, and Bleeding Woman. In these images, there is a recognizable female figure, and the composition is filled with uteruses, eggs, cords, placenta. The energy and vitality of the images contrast with the theme of neonatal loss, even though the excessive use of red brings back the idea of hemorrhage.

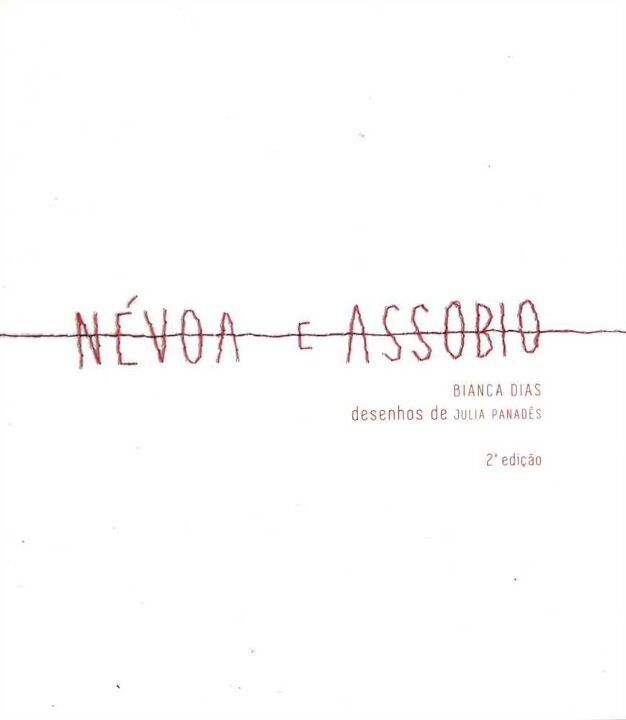

Characterized as an Artist’s Book, Bourgeois’ Ode to Oblivion displays a collage composed of fabrics and printed words on linen napkins from the artist’s wedding apparel15. Bourgeois was one of the artists studied by Panadés in her doctoral thesis defended in 2017 at UFMG. Thus, the paratextual composition in Dias’ volume, as an artist’s book, relates to Bourgeois’s gesture through the aesthetics of an artist’s book, with an apparent spine, exposing the threads of the seams of the book signatures. The book cover shows a photograph of an embroidered title in back stitch style and its back, the endpaper, reproduces the reverse side of this embroidery, simulating an actual stitched object. These paratextual and extra-diegetic details are uniquely integrated into the work of Dias and Panadés, promoting a dialogue between the account of Caetano’s brief life and the aesthetics of the editorial production characterized by the volume’s artisanal appearance. The paratext, for Genette16, comes alongside the text, and is a way of making an introduction, or of “making it present, to guarantee its [the text] presence in the world, its reception, and its consumption, in the form, at least today, of a book17”. Therefore, the paratext is a border that becomes a permeable membrane between the inside and the outside, an intermedial dispositive on its own.

Fig. 1

Reproduction of the book cover

Threaded illustrations are interposed to the verbal content as part of this editorial project. Threads and seams in their three-dimensionality are recalled, in their volume and texture, acting as an intermedial reference according to Rajewsky’s categorization. The illustrations are not literally presented as stitching on fabric, but are remediated by photography, as a simulacrum of a sewing work, which is why they are identified in the field of intermedial references. Sewing appears in writing, pictures, and joint parts of this volume. On the gesture of sewing, Edith Derdyk (2010) conceives it as an extension of her artistic work with line and thread. It is used for anchoring herself in the singularity of the incorporation of this activity in her works, she states: “[s]ewing supposes the condition of perforating the material and later join the pieces. From any continuous fabric, from any malleable and flexible material, capable of being pierced, it will be necessary to pierce, poke, tear, cut to connect this same material in another configuration18.” Sewing, thus, refers to a desire for manipulation and transformation of materials, but above all for creation, repair, and adjustment. Dias’s accounts: “In mourning and in ordinary silence, I sew the threads of these winged words in an exercise of hope19”. The frustrating experience of a denied motherhood may point to the fragmentation of the female self, and the sewing gesture may come up as an attempt to put everything together, join the pieces, to become integral again: “We are all precarious, fragmented, and strange. All beauty is convulsive20”.

Sewing and embroidery were reassessed from the 1960s onwards, when they began to occupy artistic spaces with greater visibility. According to the studies by Rozsika Parker21, embroidery and sewing were part of the private sphere of the domestic scenario and occupied a place of decorative arts. They have been configured over time as “female” activities, which have traditionally been part of the educational and social formation of women. Mainly from the 1960s onwards, when textile art began to occupy art museums, it became an ambivalent artistic practice, as it was an economic activity that freed women and an artistic language linked to the feminine, but also one that confined women to the limits of the house, the domestic place, also contributing to the marginalization of this art. Embroidery as a feminine ethos is recovered in Névoa and Assobio to illustrate shapes and letters bringing with them meanings associated to feminine creation, such as the power to bear children and to produce milk, to feed the offspring. At the same time, the stitches remind us of the surgical sutures as a trope for a search for an integral self and a desire to heal by recomposing from such a loss.

Both the letters and the sewn illustrations are media products of material and sensorial modalities. In this work, words have the same materiality of a sculptural form. Dias22 refers to words as if they had volume: “I write as an exercise of reduction, so that the words – so sacred – do not lose their thickness and power23.” This artistic modality employs materialities that evoke senses that go beyond visuality, triggering the touch. Thus, the material and sensory modalities, according to Elleström24, are also important categories mobilized in Névoa and Assobio.

Even though the embroidered letters and illustrations appear to be so real, the embroidery is an effect and it is only evoked by photography, which can be associated with the field of intermedial references by Irina Rajewsky25, as mentioned above. In this category, Rajewsky states that a work can evoke or imitate elements of a medium through specific means of another medium, which is the case of photographs of Panadés’ illustrations that make up the graphic design of the book. Although the original illustrations by Panadés were made on paper, using thread and sanguine, exploring the right and reverse sides, just like an embroidered piece, the books were reproduced on paper, only mimicking the effects of the seams through photography. The pictures, by the way, are of very high quality, with high resolution, to maintain the tactile effects of the line on paper. In this way, the volume and textures are evoked by the photographic images with such verisimilitude that they convey the haptic sense, a term that refers to the tactile sensations that are triggered in the brain.

What this text intends to demonstrate is that textile media play an important role that goes beyond the limits of the illustrative function of Dias’ narrative. Regarding the role of media, Jørgen Bruhn26 makes insightful considerations when he says that the aspect of mediality cannot be separated from its content, since the media are not empty message transmission conductors. In the case of Nevoa and Assobio, sewn illustrations are materialities marked by gender issues that bring back the ideas of pain, loss, repair, and amendment, all at the same time.

The use of stitching to write and to illustrate recovers the idea of writing as a gesture of inscription, scratching, and penetration as in Villém Flusser27 “every written text is in-scription”. A gesture may refer to body movements but also to actions, deeds, something made by man, according to Flusser. Writing as a gesture is beyond the observable surface in such a way that it is not a construction but penetration, an attempt to get inside and mingling with the surface. Therefore, it is with this approach that we examine the experience of this textile technique, embroidery, or stitching to illustrate: as a piercing gesture that modifies surface, creates volume and texture, and metaphorically has the power to record symbols.

Another point is the paradoxical nature of the elaboration of grief in which is activated by the impulse of (re)generative forces, oriented towards production, towards creation. The absence of Caetano becomes the very reason why he is so present in the narrative. Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht28, in his elaboration on the production of presence in language, calls attention to the effect of tangibility that comes up in communication to produce presence because it is subjected to special references. To him, any form of communication is capable of “touching” people’s bodies during the communicative process in specific and varied ways. The act of writing for Dias is a way to produce presence in face of a moment of emptiness: “I write so that I do not lose myself in the excessive emptiness of the talking, when what is imposed on me is unspeakable.29”. The death of a son is such a painful experience that the text turns into a shrine, an elegiac homage so that the absence becomes more tangible: “A small shrine of a faith on the absurd and on the intangible that I will always carry with me30”. At the same time, writing is used to elaborate emptiness: “In flesh and blood, I write to reinvent life in me and hold my absence in my arms: word after word, I get near to my gorge of emotions31”.

It is also necessary to explore the indexical nature of the stitches in Nevoa and Assobio for it reminds sutures and scars. More importantly, they point to the previous existence of wounds. Rosalind Krauss32 states that the term “index” was taken from Jakobson’s idea for the linguistic sign, which is “full of meaning” precisely because it is “empty”. The index – in opposition to the symbol and the icon – can establish meaning along the axis of a physical relationship with its referents, according to Krauss33. The indices are the marks or traces of a specific cause, and this cause is the very thing to which they refer to. Bianca Dias’ text and the illustration by Julia Panadés poeticize the void, and the sense of emptiness left by the departure of Caetano. The title of her preface is called “Acute presence” and it says: “Writing about the loss of a son is trying to build a ranch where emptiness may take place34 […])”. However, emptiness does not represent an absence of being, but a previous presence.

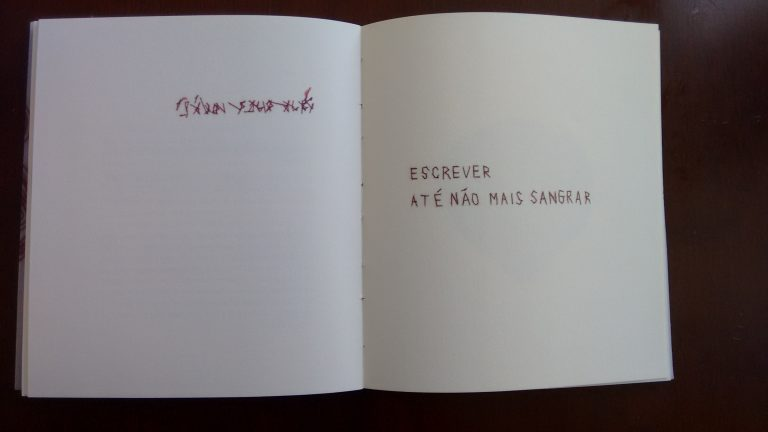

In this way, the acts of sewing and writing contain attempts to elaborate an annihilating episode that turns into an impulse of creative forces, of production. The embroidered letters of Panadés in capitals and red thread35 reveal an attempt to repair, to reorganize chaos out of the fraying experience: “I SEW THE TWO EDGES / OF THE BODY / THAT WERE OPEN / TOGETHER WITH MY AMAZEMENT36”. Sewing and writing act as restorative effects of the soul that unites parts, that organizes chaos. The sewn letter is a design and message revealing itself in its entirety, on its right and reverse side. And writing becomes a form of resistance/re-existence. Sewing and writing are integrated in gestures of elaboration of grief, in enunciative acts of transformation and acceptance.

Writing becomes not only a practice that fills in an absence but also a medium of memory, especially according to Aleida Assman37. The writing gesture in its mediality takes a central part in the eternization process because writing is a medium that survives the destructive action of time. In Nevoa e Assobio, the embroidered letters epitomize this desire to presentify an absence and materializes a token, a monument, in homage to the deceased son. It is constantly an attempt to avoid forgetfulness, oblivion. As a Foulcautian dispositive, the iconotext immortalizes Caetano and his brief existence. When Bianca Dias retells her story, her account stores her memory of the baby boy at the same time it registers her moments with him as a promise for later recollection. In a certain way, what is at stake is the fear to be forgotten, to be obliterated throughout time, that has the power to destroy memory.

This work, therefore, is masterfully configured in creative acts that rely on sewing thread and writing. These activities turn into therapeutic acts of acceptance and elaboration of mourning, while the illustration reveals the reverse, the backstage of the (re)creator gesture. Romanticized motherhood is firmly struck by showing its darkest shadow, its most abject underside. However, both writing and sewing are capable of saving, as they make the enunciators agents, authors, creators of their own stories. In the words of Edith Derdyk38, she suggests to us: “sewing makes me a conductor, inaugurates times. It is clear the presence of a feeling of omnipotence allied to the terrible human condition of lack of control over the course of things. The crack that opens from this mismatch is a field of possibilities39.”

Fig. 2

Reproduction of the front and reverse side of the embroidered text by the artist Julia Panadés.